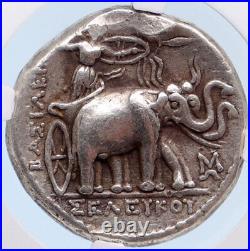

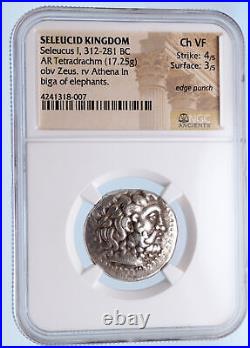

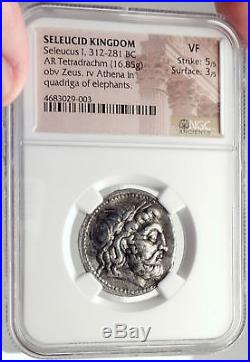

Item: i61980 Authentic Ancient Coin of. Nero – Roman Emperor: 54-68 A. Billon Silver Tetradrachm 24mm (11.79 grams) Struck at city of Alexandria in Egypt Regnal Year 12 = 65/66 A. D Reference: Milne 238; Köln 172-174; Curtis 36-54; Dattari 204; SGI 633; RPC I 5289; Sear 5 #2004 Certification: NGC Ancients VF 4529163-008 NEP KAY KAI EB EP, Radiate bust right, wearing aegis AYTOKPA, draped bust of Alexandria right in elephant skin headdress, LIB to right. Billon is an alloy of a precious metal (most commonly silver) with a majority base metal content (such as copper). It is used chiefly for making coins, medals, and token coins. The word comes from the French bille. The use of billon coins dates from ancient Greece through the Middle Ages. During the 6th and 5th centuries BC, some cities on Lesbos Island used coins made of 60% copper and 40% silver. Billon coins are perhaps best known from the Roman Empire, where progressive debasements of the Roman denarius and the Roman provincial tetradrachm. Alexandria was founded around a small Ancient Egyptian town c. 331 BC by Alexander the Great. It became an important center of the Hellenistic civilization and remained the capital of Hellenistic and Roman and Byzantine Egypt for almost 1000 years until the Muslim conquest of Egypt in AD 641, when a new capital was founded at Fustat (later absorbed into Cairo). Hellenistic Alexandria was best known for the Lighthouse of Alexandria (Pharos), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; its Great Library (the largest in the ancient world; now replaced by a modern one); and the Necropolis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Middle Ages. Alexandria was the second most powerful city of the ancient world after Rome. Alexandria is believed to have been founded by Alexander the Great in April 331 BC. Alexander’s chief architect for the project was Dinocrates. Alexandria was intended to supersede Naucratis as a Hellenistic center in Egypt, and to be the link between Greece and the rich Nile valley. Alexandria was the intellectual and cultural center of the ancient world for some time. The city and its museum attracted many of the greatest scholars, including Greeks, Jews and Syrians. The city was later plundered and lost its significance. An Egyptian city, Rhakotis, already existed on the shore also, and later gave its name to Alexandria in the Egyptian language. It continued to exist as the Egyptian quarter of the city. After Alexander’s departure, his viceroy, Cleomenes, continued the expansion. Following a struggle with the other successors of Alexander, his general Ptolemy succeeded in bringing Alexander’s body to Alexandria, though it was eventually lost after being separated from its burial site there. Although Cleomenes was mainly in charge of overseeing Alexandria’s continuous development, the Heptastadion and the mainland quarters seem to have been primarily Ptolemaic work. Inheriting the trade of ruined Tyre and becoming the center of the new commerce between Europe and the Arabian and Indian East, the city grew in less than a generation to be larger than Carthage. In a century, Alexandria had become the largest city in the world and, for some centuries more, was second only to Rome. It became Egypt’s main Greek city, with Greek people from diverse backgrounds. Alexandria was not only a center of Hellenism, but was also home to the largest urban Jewish community in the world. The Septuagint, a Greek version of the Tanakh, was produced there. The early Ptolemies kept it in order and fostered the development of its museum into the leading Hellenistic center of learning (Library of Alexandria), but were careful to maintain the distinction of its population’s three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian. In AD 115, large parts of Alexandria were destroyed during the Kitos War, which gave Hadrian and his architect, Decriannus, an opportunity to rebuild it. In 215, the emperor Caracalla visited the city and, because of some insulting satires that the inhabitants had directed at him, abruptly commanded his troops to put to death all youths capable of bearing arms. On 21 July 365, Alexandria was devastated by a tsunami (365 Crete earthquake), an event annually commemorated years later as a day of horror. Nero – 54-68 A. Caesar, 50-54 (Under Claudius). Nero (Latin: Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ;15 December 37 – 9 June 68) was Roman Emperor from 54 to 68, and the last in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great uncle Claudius to become his heir and successor, and succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius’ death. During his reign, Nero focused much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and enhancing the cultural life of the Empire. He ordered theaters built and promoted athletic games. During his reign, the redoubtable general Corbulo conducted a successful war and negotiated peace with the Parthian Empire. His general Suetonius Paulinus crushed a revolt in Britain. Nero annexed the Bosporan Kingdom to the Empire and began the First Roman-Jewish War. In 64, most of Rome was destroyed in the Great Fire of Rome, which many Romans believed Nero himself had started in order to clear land for his planned palatial complex, the Domus Aurea. In 68, the rebellion of Vindex in Gaul and later the acclamation of Galba in Hispania drove Nero from the throne. Facing assassination, he committed suicide on 9 June 68 (the first Roman emperor to do so) His death ended the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, sparking a brief period of civil wars known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Nero’s rule is often associated with tyranny and extravagance. He is known for many executions, including that of his mother, and the probable murder by poison of his stepbrother Britannicus. He is infamously known as the Emperor who “fiddled while Rome burned” and as an early persecutor of Christians. He was known for having captured Christians to burn them in his garden at night for a source of light. This view is based on the writings of Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, the main surviving sources for Nero’s reign. Few surviving sources paint Nero in a favorable light. Some sources, though, including some mentioned above, portray him as an emperor who was popular with the common Roman people, especially in the East. Some modern historians question the reliability of ancient sources when reporting on Nero’s tyrannical acts. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus , the future Nero, was born on 15 December 37 in Antium, near Rome. He was the only son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Agrippina the Younger, sister of Emperor Caligula. Nero’s father Gnaeus was the son of Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul 16 BC) and Antonia Major. Gnaeus was thus the grandson of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul 32 BC) and probably Aemilia Lepida on his father’s side, and the grandson of Mark Antony and Octavia Minor on his mother’s side. Thus, Nero had as his paternal grandmother Antonia Maior, and also claimed more remote descent from Antonia Minor as a great-grandson-later grandson after Claudius adopted him. Through Octavia, Nero was the grandnephew of Caesar Augustus. Nero’s father had been employed as a praetor and was a member of Caligula’s staff when the latter traveled to the East (some apparently think Suetonius refers to Augustus’ adopted son Gaius Caesar here, but this is not likely). Nero’s father was described by Suetonius as a murderer and a cheat who was charged by Emperor Tiberius with treason, adultery, and incest. Tiberius died, allowing him to escape these charges. Nero’s father died of edema (“dropsy”) in 39 when Nero was two. Nero’s mother was Agrippina the Younger, a great-granddaughter of Caesar Augustus and his wife Scribonia through their daughter Julia the Elder and her husband Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Agrippina’s father, Germanicus, was a grandson of Augustus’s wife, Livia, on one side and to Mark Antony and Octavia on the other. Germanicus’ mother Antonia Minor, was a daughter of Octavia Minor and Mark Antony. Octavia was Augustus’ elder sister. Germanicus was also the adopted son of Tiberius. Agrippina poisoned her second husband Passienus Crispus, so many ancient historians also accuse her of murdering her third husband, the emperor Claudius. Coin issued under Claudius celebrating young Nero as the future emperor, c. Nero was not expected to become Emperor because his maternal uncle, Caligula, had begun his reign at the age of 25 with enough time to produce his own heir. Nero’s mother, Agrippina, lost favor with Caligula and was exiled in 39 after her husband’s death. Caligula seized Nero’s inheritance and sent him to be raised by his less wealthy aunt, Domitia Lepida, who was the mother of Valeria Messalina, Claudius’s third wife. Caligula, his wife Caesonia and their infant daughter Julia Drusilla were murdered on 24 January 41. These events led Claudius, Caligula’s uncle, to become emperor. Claudius allowed Agrippina to return from exile. Claudius had married twice before marrying Valeria Messalina. His previous marriages produced three children including a son, Drusus, who died at a young age. He had two children with Messalina – Claudia Octavia (born 40) and Britannicus (born 41). Messalina was executed by Claudius in the year 48. In 49 AD, Claudius married a fourth time, to Nero’s mother Agrippina. To aid Claudius politically, young Nero was adopted in 50 and took the name Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus. Nero was older than his stepbrother Britannicus, and thus became heir to the throne. Nero was proclaimed an adult in 51 at the age of 14. He was appointed proconsul, entered and first addressed the Senate, made joint public appearances with Claudius, and was featured in coinage. In 53, he married his stepsister Claudia Octavia. Agrippina crowns her young son Nero with a laurel wreath. She carries a cornucopia, symbol of fortune and plenty, and he wears the armour and cloak of a Roman commander, with a helmet on the ground at his feet. The scene refers to Nero’s accession as emperor in 54 AD and is dated before 59 AD when Nero had Agrippina murdered. Claudius died in 54 and Nero, taking the name Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus , was established as Emperor. Though accounts vary, many ancient historians state Agrippina poisoned Claudius. According to Pliny the Elder, she used poison mushrooms. It is not known how much Nero knew or if he was even involved in the death of Claudius. For even if he was not the instigator of the emperor’s death, he was at least privy to it, as he openly admitted; for he used afterwards to laud mushrooms, the vehicle in which the poison was administered to Claudius, as “the food of the gods, ” as the Greek proverb has it. At any rate, after Claudius’ death he vented on him every kind of insult, in act and word, charging him now with folly and now with cruelty; for it was a favourite joke of his to say that Claudius had ceased to play the fool among mortals, lengthening the first syllable of the word morari, and he disregarded many of his decrees and acts as the work of a madman and a dotard. Finally, he neglected to enclose the place where his body was burned except with a low and mean wall. Nero became Emperor at 17 when the news of Claudius’ death was made known, the youngest emperor until that time. Ancient historians describe Nero’s early reign as being strongly influenced by his mother, Agrippina, his tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca, and the Praetorian Prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus, especially in the first year. Other tutors were less often mentioned, such as Alexander of Aegae. Very early in Nero’s rule, problems arose from competition for influence between Agrippina and Nero’s two main advisers, Seneca and Burrus. In 54, Agrippina tried to sit down next to Nero while he met with an Armenian envoy, but Seneca stopped her and prevented a scandalous scene (as it was unimaginable at that time for a woman to be in the same room as men doing official business). Nero’s friends also mistrusted Agrippina and told Nero to beware of his mother. Nero was reportedly unsatisfied with his marriage to Octavia and entered into an affair with Claudia Acte, a former slave. In 55, Agrippina attempted to intervene in favor of Octavia and demanded that her son dismiss Acte. Nero, with the support of Seneca, resisted the intervention of his mother in his personal affairs. With Agrippina’s influence over her son severed, she reportedly began pushing for Britannicus, Nero’s stepbrother, to become emperor. Nearly fifteen-year-old Britannicus, heir-designate prior to Nero’s adoption, was still legally a minor, but was approaching legal adulthood. According to Tacitus, Agrippina hoped that with her support, Britannicus, being the blood son of Claudius, would be seen as the true heir to the throne by the state over Nero. However, the youth died suddenly and suspiciously on 12 February 55, the very day before his proclamation as an adult had been set. Nero claimed that Britannicus died from an epileptic seizure, but ancient historians all claim Britannicus’ death came from Nero’s poisoning him. Supposedly, he enlisted the services of Locusta, a woman who specialized in the manufacture of poisons. She devised a mixture to kill Britannicus, but after testing it unsuccessfully on a slave, Nero angrily threatened to have her put to death if she did not come up with something usable. Locusta then devised a new concoction that she promised would kill swifter than a viper. Her promise was fulfilled after Britannicus consumed it at a dinner party from water used to cool his wine, which had already been tasted, and succumbed within minutes. After the death of Britannicus, Agrippina was accused of slandering Octavia and Nero ordered her out of the imperial residence. Matricide and consolidation of power. Coin of Nero and Poppaea Sabina. Over time, Nero became progressively more powerful, freeing himself of his advisers and eliminating rivals to the throne. In 55, he removed Marcus Antonius Pallas, an ally of Agrippina, from his position in the treasury. Pallas, along with Burrus, was accused of conspiring against the Emperor to bring Faustus Sulla to the throne. Seneca was accused of having relations with Agrippina and embezzlement. Seneca succeeded in having himself, Pallas and Burrus acquitted. According to Cassius Dio, at this time, Seneca and Burrus reduced their role in governing from careful management to mere moderation of Nero. In 58, Nero became romantically involved with Poppaea Sabina, the wife of his friend and future emperor Otho. Reportedly because a marriage to Poppaea and a divorce from Octavia did not seem politically feasible with Agrippina alive, Nero ordered the murder of his mother in 59. A number of modern historians find this an unlikely motive as Nero did not marry Poppaea until 62. Additionally, according to Suetonius, Poppaea did not divorce her husband until after Agrippina’s death, making it unlikely that the already married Poppaea would be pressing Nero for marriage. Some modern historians theorize that Nero’s execution of Agrippina was prompted by her plotting to set Rubellius Plautus on the throne. According to Suetonius, Nero tried to kill his mother through a planned shipwreck, which took the life of her friend, Acerronia Polla, but when Agrippina survived, he had her executed and framed it as a suicide. The incident is also recorded by Tacitus. The Remorse of the Emperor Nero after the Murder of his Mother , by John William Waterhouse, 1878. In 62, Nero’s adviser, Burrus, died. Additionally, Seneca was again faced with embezzlement charges. Seneca asked Nero for permission to retire from public affairs. Nero divorced and banished Octavia on grounds of infertility, leaving him free to marry the pregnant Poppaea. After public protests, Nero was forced to allow Octavia to return from exile, but she was executed shortly after her return. Nero also was reported to have kicked Poppaea to death in 65 before she could have his second child. However, modern historians, noting Suetonius, Tacitus and Cassius Dio’s possible bias against Nero and the likelihood that they did not have eyewitness accounts of private events, postulate that Poppaea may have died because of complications of miscarriage or childbirth. Accusations of treason being plotted against Nero and the Senate first appeared in 62. The Senate ruled that Antistius, a praetor, should be put to death for speaking ill of Nero at a party. Later, Nero ordered the exile of Fabricius Veiento who slandered the Senate in a book. Tacitus writes that the roots of the conspiracy led by Gaius Calpurnius Piso began in this year. To consolidate power, Nero executed a number of people in 62 and 63 including his rivals Pallas, Rubellius Plautus and Faustus Sulla. According to Suetonius, Nero “showed neither discrimination nor moderation in putting to death whomsoever he pleased” during this period. Nero’s consolidation of power also included a slow usurping of authority from the Senate. In 54, Nero promised to give the Senate powers equivalent to those under Republican rule. By 65, senators complained that they had no power left and this led to the Pisonian conspiracy. When Nero’s wife Poppaea Sabina died in 65, Nero went into deep mourning. Her body was not cremated, it was stuffed with spices, embalmed and put in the Mausoleum of Augustus. She was given a state funeral. Nero praised her during the funeral eulogy and gave her divine honors. It is said that Nero burned ten years’ worth of Arabia’s incense production at her funeral. In the beginning of 66, he married Statilia Messalina. She was already married when she became Nero’s mistress in 65 AD, with Statilia’s husband being driven to suicide in 66, so Nero could marry Statilia. She was one of the few of Nero’s courtiers who survived the fall of his reign. In 67, Nero ordered a young freedman, Sporus, to be castrated and then married him. According to Dion Cassius, Sporus bore an uncanny resemblance to Sabina, and Nero even called him by his dead wife’s name. Over the course of his reign, Nero often made rulings that pleased the lower class. Nero was criticized as being obsessed with personal popularity. Nero began his reign in 54 by promising the Senate more autonomy. In this first year, he forbade others to refer to him with regard to enactments, for which he was praised by the Senate. Nero was known for spending his time visiting brothels and taverns during this period. In 55, Nero began taking on a more active role as an administrator. He was consul four times between 55 and 60. During this period, some ancient historians speak fairly well of Nero and contrast it with his later rule. Under Nero, restrictions were put on the amount of bail and fines. There was a discussion in the Senate on the misconduct of the freedmen class, and a strong demand was made that patrons should have the right of revoking freedom. Nero supported the freedmen and ruled that patrons had no such right. The Senate tried to pass a law in which the crimes of one slave applied to all slaves within a household. Despite riots from the people, Nero supported the Senate on their measure, and deployed troops to organise the execution of 400 slaves affected by the law. However, he vetoed strong measures against the freedmen affected by the case. Nero banned any magistrate or procurator from exhibiting public entertainment for fear that the venue was being used as a method to sway the populace. Additionally, there were many impeachments and removals of government officials along with arrests for extortion and corruption. The Senate convinced him this action would bankrupt the public treasury. In imitation of the Greeks, Nero built a number of gymnasiums and theatres. Enormous gladiatorial shows were also held. Nero also established the quinquennial Neronia. The festival included games, poetry, and theater. Historians indicate that there was a belief that theatre led to immorality. Others considered that to have performers dressed in Greek clothing was old fashioned. Some questioned the large public expenditure on entertainment. In 64, Rome burned. Nero enacted a public relief effort as well as significant reconstruction. A number of other major construction projects occurred in Nero’s late reign. Nero had the marshes of Ostia filled with rubble from the fire. He erected the large Domus Aurea. In 67, Nero attempted to have a canal dug at the Isthmus of Corinth. Ancient historians state that these projects and others exacerbated the drain on the State’s budget. The cost to rebuild Rome was immense, requiring funds the state treasury did not have. Nero devalued the Roman currency for the first time in the Empire’s history. He reduced the weight of the denarius from 84 per Roman pound to 96 (3.85 grams to 3.35 grams). He also reduced the silver purity from 99.5% to 93.5%-the silver weight dropping from 3.83 grams to 3.4 grams. Furthermore, Nero reduced the weight of the aureus from 40 per Roman pound to 45 (8 grams to 7.2 grams). Between 62 and 67, according to Plinius the Elder and Seneca, Nero promoted an expedition to discover the sources of the Nile River. It was the first exploration of equatorial Africa from Europe in history. However, Nero’s expedition up the Nile failed because water plants had clogged the river, denying Nero’s vessels access to the Sudd of Nubia. The economic policy of Nero is a point of debate among scholars. Modern historians, though, note that the period was riddled with deflation and that it is likely that Nero’s spending came in the form of public works projects and charity intended to ease economic troubles. Great Fire of Rome (64 AD). The Great Fire of Rome erupted on the night of 18 July to 19 July 64. Artwork depicting the Great Fire of Rome. The extent of the fire is uncertain. According to Tacitus, who was nine at the time of the fire, it spread quickly and burned for over five days. It destroyed three of fourteen Roman districts and severely damaged seven. The only other historian who lived through the period and mentioned the fire is Pliny the Elder, who wrote about it in passing. Other historians who lived through the period (including Josephus, Dio Chrysostom, Plutarch, and Epictetus) make no mention of it in what remains of their work. It is uncertain who or what actually caused the fire-whether accident or arson. Suetonius and Cassius Dio favor Nero as the arsonist, so he could build a palatial complex. Tacitus mentions that Christians confessed to the crime, but it is not known whether these confessions were induced by torture. However, accidental fires were common in ancient Rome. In fact, Rome suffered another large fire in 69 and in 80. It was said by Suetonius and Cassius Dio that Nero sang the “Sack of Ilium” in stage costume while the city burned. Popular legend claims that Nero played the fiddle at the time of the fire, an anachronism based merely on the concept of the lyre, a stringed instrument associated with Nero and his performances. There were no fiddles in 1st-century Rome. Tacitus’s account, however, has Nero in Antium at the time of the fire. Tacitus also said that Nero playing his lyre and singing while the city burned was only rumor. Nero’s contributions to the relief extended to personally taking part in the search for and rescue of victims of the blaze, spending days searching the debris without even his bodyguards. After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors. In the wake of the fire, he made a new urban development plan. Houses after the fire were spaced out, built in brick, and faced by porticos on wide roads. Nero also built a new palace complex known as the Domus Aurea in an area cleared by the fire. This included lush artificial landscapes and a 30-meter-tall statue of himself, the Colossus of Nero. The size of this complex is debated (from 100 to 300 acres). To find the necessary funds for the reconstruction, tributes were imposed on the provinces of the empire. Tacitus notes that the population searched for a scapegoat and rumors held Nero responsible. To deflect blame, Nero targeted Christians. He ordered Christians to be thrown to dogs, while others were crucified and burned. Nero enjoyed driving a one-horse chariot, singing to the lyre, and poetry. He even composed songs that were performed by other entertainers throughout the empire. At first, Nero only performed for a private audience. Nero began singing in public in Neapolis in order to improve his popularity. He also sang at the second quinquennial Neronia in 65. It was said that Nero craved the attention, but historians also write that Nero was encouraged to sing and perform in public by the Senate, his inner circle and the people. Ancient historians strongly criticize his choice to perform, calling it shameful. Nero was convinced to participate in the Olympic Games of 67 in order to improve relations with Greece and display Roman dominance. As a competitor, Nero raced a ten-horse chariot and nearly died after being thrown from it. He also performed as an actor and a singer. The victories are attributed to Nero bribing the judges and his status as emperor. War and peace with Parthia. Shortly after Nero’s accession to the throne in 54, the Roman vassal kingdom of Armenia overthrew their Iberian prince Rhadamistus and he was replaced with the Parthian prince Tiridates. This was seen as a Parthian invasion of Roman territory. There was concern in Rome over how the young Emperor would handle the situation. Nero reacted by immediately sending the military to the region under the command of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. The Parthians temporarily relinquished control of Armenia to Rome. The peace did not last and full-scale war broke out in 58. The Parthian king Vologases I refused to remove his brother Tiridates from Armenia. The Parthians began a full-scale invasion of the Armenian kingdom. Commander Corbulo responded and repelled most of the Parthian army that same year. Tiridates retreated and Rome again controlled most of Armenia. Nero was acclaimed in public for this initial victory. Tigranes, a Cappadocian noble raised in Rome, was installed by Nero as the new ruler of Armenia. Corbulo was appointed governor of Syria as a reward. In 62, Tigranes invaded the Parthian province of Adiabene. Again, Rome and Parthia were at war and this continued until 63. Parthia began building up for a strike against the Roman province of Syria. Corbulo tried to convince Nero to continue the war, but Nero opted for a peace deal instead. There was anxiety in Rome about eastern grain supplies and a budget deficit. The result was a deal where Tiridates again became the Armenian king, but was crowned in Rome by Emperor Nero. In the future, the king of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans. Tiridates was forced to come to Rome and partake in ceremonies meant to display Roman dominance. This peace deal of 63 was a considerable victory for Nero politically. Nero became very popular in the eastern provinces of Rome and with the Parthians as well. The peace between Parthia and Rome lasted 50 years until Emperor Trajan of Rome invaded Armenia in 114. Other major power struggles and rebellions. A plaster bust of Nero, Pushkin Museum, Moscow. The war with Parthia was not Nero’s only major war but he was both criticized and praised for an aversion to battle. Like many emperors, Nero faced a number of rebellions and power struggles within the empire. British Revolt of 60-61 (Boudica’s Uprising). In 60, a major rebellion broke out in the province of Britannia. While the governor Gaius Suetonius Paullinus and his troops were busy capturing the island of Mona (Anglesey) from the druids, the tribes of the southeast staged a revolt led by queen Boudica of the Iceni. Boudica and her troops destroyed three cities before the army of Paullinus could return, receive reinforcements, and quell the rebellion in 61. Fearing Paullinus himself would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced him with the more passive Publius Petronius Turpilianus. The Pisonian Conspiracy of 65. In 65, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, a Roman statesman, organized a conspiracy against Nero with the help of Subrius Flavus and Sulpicius Asper, a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard. According to Tacitus, many conspirators wished to “rescue the state” from the emperor and restore the Republic. The freedman Milichus discovered the conspiracy and reported it to Nero’s secretary, Epaphroditos. As a result, the conspiracy failed and its members were executed including Lucan, the poet. Nero’s previous advisor, Seneca was ordered to commit suicide after admitting he discussed the plot with the conspirators. The First Jewish War of 66-70. In 66, there was a Jewish revolt in Judea stemming from Greek and Jewish religious tension. In 67, Nero dispatched Vespasian to restore order. This revolt was eventually put down in 70, after Nero’s death. This revolt is famous for Romans breaching the walls of Jerusalem and destroying the Second Temple of Jerusalem. The revolt of Vindex and Galba and the death of Nero. Lucius Verginius Rufus, the governor of Germania Superior, was ordered to put down Vindex’s rebellion. In an attempt to gain support from outside his own province, Vindex called upon Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, to join the rebellion and further, to declare himself emperor in opposition to Nero. At the Battle of Vesontio in May 68, Verginius’ forces easily defeated those of Vindex and the latter committed suicide. However, after putting down this one rebel, Verginius’ legions attempted to proclaim their own commander as Emperor. Verginius refused to act against Nero, but the discontent of the legions of Germany and the continued opposition of Galba in Spain did not bode well for Nero. While Nero had retained some control of the situation, support for Galba increased despite his being officially declared a public enemy. The prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Gaius Nymphidius Sabinus, also abandoned his allegiance to the Emperor and came out in support for Galba. In response, Nero fled Rome with the intention of going to the port of Ostia and, from there, to take a fleet to one of the still-loyal eastern provinces. However, he abandoned the idea when some army officers openly refused to obey his commands, responding with a line from Vergil’s Aeneid : Is it so dreadful a thing then to die? ” Nero then toyed with the idea of fleeing to Parthia, throwing himself upon the mercy of Galba, or to appeal to the people and beg them to pardon him for his past offences “and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the prefecture of Egypt. Suetonius reports that the text of this speech was later found in Nero’s writing desk, but that he dared not give it from fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum. After sleeping, he awoke at about midnight to find the palace guard had left. Dispatching messages to his friends’ palace chambers for them to come, he received no answers. Upon going to their chambers personally, he found them all abandoned. When he called for a gladiator or anyone else adept with a sword to kill him, no one appeared. He cried, Have I neither friend nor foe? And ran out as if to throw himself into the Tiber. Returning, Nero sought for some place where he could hide and collect his thoughts. An imperial freedman, Phaon, offered his villa, located 4 miles outside the city. Travelling in disguise, Nero and four loyal freedman, Epaphroditos, Phaon, Neophytus, and Sporus, reached the villa, where Nero ordered them to dig a grave for him. At this time, a courier arrived with a report that the Senate had declared Nero a public enemy and that it was their intention to execute him by beating him to death. At this news, Nero prepared himself for suicide. Losing his nerve, he first begged for one of his companions to set an example by first killing himself. At last, the sound of approaching horsemen drove Nero to face the end. However, he still could not bring himself to take his own life but instead he forced his private secretary, Epaphroditos, to perform the task. Nero’s famous dying words were “Qualis artifex pereo, ” which translates into English as What an artist dies in me! Events and revolts leading up to Nero’s death are portrayed in the 1951 film, Quo Vadis, with Peter Ustinov playing Nero. When one of the horsemen entered, upon his seeing Nero all but dead he attempted to stop the bleeding in vain. Nero died on 9 June 68, the anniversary of the death of Octavia, and was buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, in what is now the Villa Borghese (Pincian Hill) area of Rome. With his death, the Julio-Claudian dynasty ended. Chaos ensued in the year of the Four Emperors. According to Suetonius and Cassius Dio, the people of Rome celebrated the death of Nero. Tacitus, though, describes a more complicated political environment. Tacitus mentions that Nero’s death was welcomed by Senators, nobility and the upper class. The lower-class, slaves, frequenters of the arena and the theater, and “those who were supported by the famous excesses of Nero”, on the other hand, were upset with the news. Members of the military were said to have mixed feelings, as they had allegiance to Nero, but were bribed to overthrow him. Eastern sources, namely Philostratus II and Apollonius of Tyana, mention that Nero’s death was mourned as he “restored the liberties of Hellas with a wisdom and moderation quite alien to his character” and that he held our liberties in his hand and respected them. Modern scholarship generally holds that, while the Senate and more well-off individuals welcomed Nero’s death, the general populace was loyal to the end and beyond, for Otho and Vitellius both thought it worthwhile to appeal to their nostalgia. Nero’s name was erased from some monuments, in what Edward Champlin regards as an “outburst of private zeal”. Many portraits of Nero were reworked to represent other figures; according to Eric R. Varner, over fifty such images survive. This reworking of images is often explained as part of the way in which the memory of disgraced emperors was condemned posthumously (see damnatio memoriae). Champlin, however, doubts that the practice is necessarily negative and notes that some continued to create images of Nero long after his death. The civil war during the year of the Four Emperors was described by ancient historians as a troubling period. According to Tacitus, this instability was rooted in the fact that emperors could no longer rely on the perceived legitimacy of the imperial bloodline, as Nero and those before him could. Galba began his short reign with the execution of many allies of Nero and possible future enemies. One such notable enemy included Nymphidius Sabinus, who claimed to be the son of Emperor Caligula. Otho was said to be liked by many soldiers because he had been a friend of Nero’s and resembled him somewhat in temperament. It was said that the common Roman hailed Otho as Nero himself. Otho used “Nero” as a surname and reerected many statues to Nero. Vitellius began his reign with a large funeral for Nero complete with songs written by Nero. After Nero’s suicide in 68, there was a widespread belief, especially in the eastern provinces, that he was not dead and somehow would return. This belief came to be known as the Nero Redivivus Legend. The legend of Nero’s return lasted for hundreds of years after Nero’s death. Augustine of Hippo wrote of the legend as a popular belief in 422. At least three Nero imposters emerged leading rebellions. The first, who sang and played the cithara or lyre and whose face was similar to that of the dead emperor, appeared in 69 during the reign of Vitellius. After persuading some to recognize him, he was captured and executed. Sometime during the reign of Titus (79-81), another impostor appeared in Asia and sang to the accompaniment of the lyre and looked like Nero but he, too, was killed. Twenty years after Nero’s death, during the reign of Domitian, there was a third pretender. He was supported by the Parthians, who only reluctantly gave him up, and the matter almost came to war. In his book The Lives of the Twelve Caesars , Suetonius describes Nero as about the average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender. The history of Nero’s reign is problematic in that no historical sources survived that were contemporary with Nero. These first histories at one time did exist and were described as biased and fantastical, either overly critical or praising of Nero. The original sources were also said to contradict on a number of events. Nonetheless, these lost primary sources were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Nero written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporary historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus, Cluvius Rufus and Pliny the Elder all wrote condemning histories on Nero that are now lost. There were also pro-Nero histories, but it is unknown who wrote them or for what deeds Nero was praised. The bulk of what is known of Nero comes from Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio, who were all of the senatorial class. Tacitus and Suetonius wrote their histories on Nero over fifty years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 150 years after Nero’s death. These sources contradict on a number of events in Nero’s life including the death of Claudius, the death of Agrippina, and the Roman fire of 64, but they are consistent in their condemnation of Nero. At the end of 66, conflict broke out between Greeks and Jews in Jerusalem and Caesarea. According to the Talmud, Nero went to Jerusalem and shot arrows in all four directions. All the arrows landed in the city. He then asked a passing child to repeat the verse he had learned that day. The child responded, “I will lay my vengeance upon Edom by the hand of my people Israel” Ez. Nero became terrified, believing that God wanted the Temple in Jerusalem to be destroyed, but would punish the one to carry it out. Nero said, “He desires to lay waste His House and to lay the blame on me, ” whereupon he fled and converted to Judaism to avoid such retribution. Vespasian was then dispatched to put down the rebellion. The Talmud adds that the sage Reb Meir Baal HaNess, a prominent supporter of the Bar Kokhba rebellion against Roman rule, was a descendant of Nero. Roman and Greek sources nowhere report Nero’s alleged trip to Jerusalem or his alleged conversion to Judaism. There is also no record of Nero having any offspring who survived infancy: his only recorded child, Claudia Augusta, died aged 4 months. Christian tradition and secular historical sources hold Nero as the first major state sponsor of Christian persecution, and sometimes as the killer of Apostles Peter and Paul. Some 2nd- and 3rd-century theologians, among others, recorded their belief that Nero would return from death or exile, usually as the Anti-Christ. He is also seen as one of the most savage persecutors of Christians. Non-Christian historian Tacitus describes Nero extensively torturing and executing Christians after the fire of 64. Suetonius also mentions Nero punishing Christians, though he does so as a praise and does not connect it with the fire. Christian writer Tertullian c. 155-230 was the first to call Nero the first persecutor of Christians. He wrote, Examine your records. There you will find that Nero was the first that persecuted this doctrine. 240-320 also said that Nero “first persecuted the servants of God”. As does Sulpicius Severus. However, Suetonius writes that, “since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he [emperor Claudius] expelled them from Rome” (” Iudaeos impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantis Roma expulit “). These expelled “Jews” may have been early Christians, although Suetonius is not explicit. Nor is the Bible explicit, calling Aquila of Pontus and his wife, Priscilla, both expelled from Italy at the time, Jews. Killer of Peter and Paul. The first text to suggest that Nero killed an apostle is the apocryphal Ascension of Isaiah , a Christian writing from the 2nd century. It says, the slayer of his mother, who himself this king, will persecute the plant which the Twelve Apostles of the Beloved have planted. Of the Twelve one will be delivered into his hands. Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea c. 275-339 was the first to write that Paul was beheaded in Rome during the reign of Nero. He states that Nero’s persecution led to Peter and Paul’s deaths, but that Nero did not give any specific orders. Several other accounts have Paul surviving his two years in Rome and traveling to Hispania. Peter is first said to have been crucified upside-down in Rome during Nero’s reign (but not by Nero) in the apocryphal Acts of Peter c. The account ends with Paul still alive and Nero abiding by God’s command not to persecute any more Christians. By the 4th century, a number of writers were stating that Nero killed Peter and Paul. The Ascension of Isaiah is the first text to suggest that Nero was the Antichrist. It claims that a lawless king, the slayer of his mother… Will come and there will come with him all the powers of this world, and they will hearken unto him in all that he desires. The Sibylline Oracles, Book 5 and 8, written in the 2nd century, speak of Nero returning and bringing destruction. Within Christian communities, these writings, along with others, fueled the belief that Nero would return as the Antichrist. In 310, Lactantius wrote that Nero suddenly disappeared, and even the burial-place of that noxious wild beast was nowhere to be seen. This has led some persons of extravagant imagination to suppose that, having been conveyed to a distant region, he is still reserved alive; and to him they apply the Sibylline verses. In 422, Augustine of Hippo wrote about 2 Thessalonians 2:1-11, where he believed Paul mentioned the coming of the Antichrist. Though he rejects the theory, Augustine mentions that many Christians believed that Nero was the Antichrist or would return as the Antichrist. He wrote, so that in saying, “For the mystery of iniquity doth already work, ” he alluded to Nero, whose deeds already seemed to be as the deeds of Antichrist. Some modern biblical scholars such as Delbert Hillers (Johns Hopkins University) of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the editors of the Oxford & Harper Collins Study Bibles, contend that the number 666 in the Book of Revelation is a code for Nero, a view that is also supported in Roman Catholic Biblical commentaries. The concept of Nero as the Antichrist is often a central belief of Preterist eschatology. Ilya Zlobin, world-renowned expert numismatist, enthusiast, author and dealer in authentic ancient Greek, ancient Roman, ancient Byzantine, world coins & more. Ilya Zlobin is an independent individual who has a passion for coin collecting, research and understanding the importance of the historical context and significance all coins and objects represent. Send me a message about this and I can update your invoice should you want this method. Getting your order to you, quickly and securely is a top priority and is taken seriously here. Great care is taken in packaging and mailing every item securely and quickly. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Additionally, the coin is inside it’s own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2×2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. Whether your goal is to collect or give the item as a gift, coins presented like this could be more prized and valued higher than items that were not given such care and attention to. When should I leave feedback? Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens sometimes that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for their order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. How and where do I learn more about collecting ancient coins? Visit the “Guide on How to Use My Store” for on an overview about using my store, with additional information and links to all other parts of my store which may include educational information on topics you are looking for. The item “NERO 65AD Alexandria Elephant Silver Tetradrachm Ancient Roman Coin NGC i61980″ is in sale since Monday, May 29, 2017. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ Ancient\Roman\ Provincial (100-400 AD)”. The seller is “highrating_lowprice” and is located in Rego Park, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Certification: NGC

- Coin Type: Ancient Roman

- Grade: VF

- Certification Number: 4529163-008