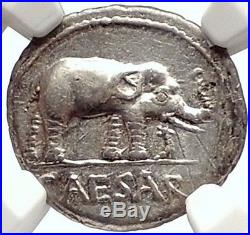

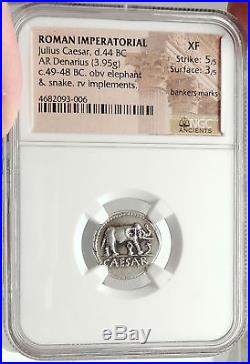

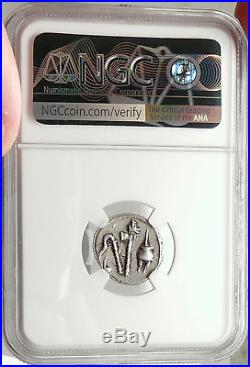

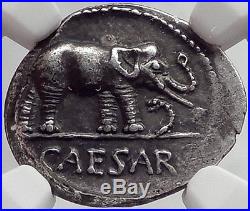

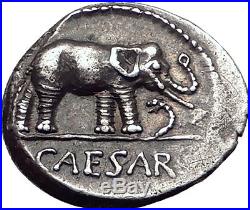

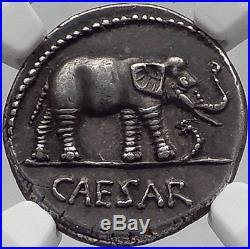

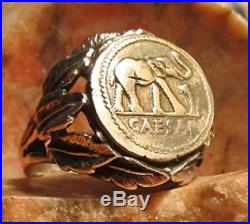

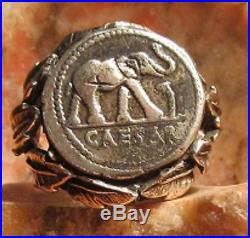

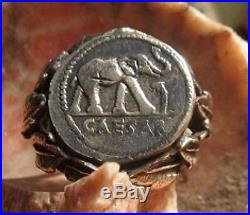

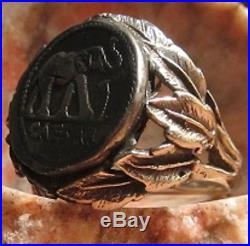

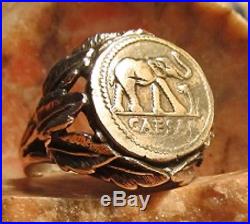

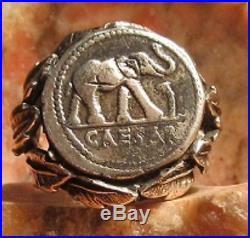

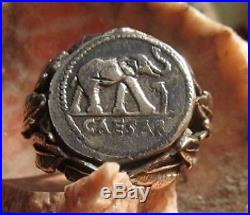

Item: i69582 Authentic Ancient Coin of. As Dictator: 49-44 B. Roman General, Politician, Hero & Dictator Silver Denarius 17mm (3.99 grams) Military mint traveling with Caesar in northern Italy, struck circa 49-48 B. Reference: RSC 49; Crawford 443/1; CRI 9; Sydenham 1006 Pedigree / Provenance. Acquired from P&P Santamaria in the 1950s. Ch AU Strike: 4/5 Surface: 3/5 4625702-001 Elephant advancing right, trampling horned serpent; CAESAR in exergue. Simpulum (ladle), aspergillum (sprinkler), securis (axe surmounted by dog or wolf’s head), and apex (flamen’s cap). The obverse type may symbolize Caesar’s victory over evil, whereas the reverse refers to Caesar’s office of Pontifex Maximus. Symbolism of the Elephant. The representation of this animal frequently occurs on Roman coins. The head, and sometimes the proboscis only, on an Elephant is a symbol of Africa. An Elephant trampling on a serpent with it’s fore feet, is the well-known type on the denarius of Julius Caesar. But it has given rise from it’s name in that region; the animal being called in the Punic language Caesar, this name became appropriated to the family. “But” says Echhel vi. 5 and 6, in noticing these conflicting opinions prior to this grandfather of Julius, we find in Livy the cognomen of Caesar. Now, if that be true, which is stated by Constantinus Manasses, that’elephants are called Caesares by the Phoenicians,’ and which, as we have just observed, is confirmed by Servius and Spartian, the present elephant would be an allusion to the name; as, moreover, it is represented as trampling on a serpent, with which reptile, according to Pliny, the elephant is at perpetual feud; and as it is established by Artemidorus, that the elephant in Italy denotes a lord, a king, or a man in high authority; we shall then recognize a type flattering to the ambition of Caesar, and by which he was desirous to intimate his victory over the barbarians, and all who were envious of his glory. Whatever may be the decision on this point, the type may be considered as a presage of future dominion. For the elephant, independently of its uses in war and amphitheatre, was an undoubted symbol of honor or of arrogance. According to Suetonius In Nerone, chap. Domitius, the ancestor of Nero, after his victory, during his consulate, over the Allobroges, was carried through the province on an elephant, preceded by a large body of troops, as in the solemnity of a triumph. Julius Caesar himself, when his military toils were over, ascended the Capitol, lighted by forty elephants, bearing torches, on either side of him. Lastly, there was no special use for elephants, except to draw the imperial thensae at funerals, or the chariots of the Caesars, either in a triumph, or in their consular processions. Elephants are represented on coins as an emblem of Eternity, it has been among the vulgar errors of the ancients to believe that those stupendous creatures lived two or even three hundred years. It was, however, on the known longevity of the elephant (exceeding, as Pliny, quoting Aristotle, says, that of all other animals), that they were employed in the funeral processions of emperors and empresses, on the occasion of their apotheosis. Gaius Julius Caesar (13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman military and political leader. He played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. As a politician, Caesar made use of popularist tactics. During the late 60s and into the 50s BC, he formed political alliances that led to the so-called First Triumvirate, an extra-legal arrangement with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) that was to dominate Roman politics for several years. Their factional attempts to amass power for themselves were opposed within the Roman Senate by the optimates, among them Marcus Porcius Cato and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, with the sometime support of Marcus Tullius Cicero. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul extended the Roman world to the North Sea, and in 55 BC he also conducted the first Roman invasion of Britain. These achievements granted him unmatched military power and threatened to eclipse Pompey’s, while the death of Crassus contributed to increasing political tensions between the two triumviral survivors. Political realignments in Rome finally led to a stand-off between Caesar and Pompey, the latter having taken up the cause of the Senate. With the order that sent his legions across the Rubicon, Caesar began a civil war in 49 BC from which he emerged as the unrivaled leader of the Roman world. After assuming control of government, he began extensive reforms of Roman society and government. He centralised the bureaucracy of the Republic and was eventually proclaimed “dictator in perpetuity” (dictator perpetuo). A group of senators, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, assassinated the dictator on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, hoping to restore the normal running of the Republic. However, the result was another Roman civil war, which ultimately led to the establishment of a permanent autocracy by Caesar’s adopted heir, Gaius Octavianus. In 42 BC, two years after his assassination, the Senate officially sanctified Caesar as one of the Roman deities. Much of Caesar’s life is known from his own Commentaries (Commentarii) on his military campaigns, and other contemporary sources such as the letters and speeches of his political rival Cicero, the historical writings of Sallust, and the poetry of Catullus. Many more details of his life are recorded by later historians, such as Appian, Suetonius, Plutarch, Cassius Dio and Strabo. Caesar was born into a patrician family, the gens Julia , which claimed descent from Iulus, son of the legendary Trojan prince Aeneas, supposedly the son of the goddess Venus. The cognomen “Caesar” originated, according to Pliny the Elder, with an ancestor who was born by caesarean section (from the Latin verb to cut, caedere , caes-). The Historia Augusta suggests three alternative explanations: that the first Caesar had a thick head of hair (Latin caesaries); that he had bright grey eyes (Latin oculis caesiis); or that he killed an elephant (caesai in Moorish) in battle. Caesar issued coins featuring images of elephants, suggesting that he favoured this interpretation of his name. Despite their ancient pedigree, the Julii Caesares were not especially politically influential, having produced only three consuls. Caesar’s father, also called Gaius Julius Caesar, reached the rank of praetor, the second highest of the Republic’s elected magistracies, and governed the province of Asia, perhaps through the influence of his prominent brother-in-law Gaius Marius. His mother, Aurelia Cotta, came from an influential family which had produced several consuls. Marcus Antonius Gnipho, an orator and grammarian of Gaulish origin, was employed as Caesar’s tutor. Caesar had two sisters, both called Julia. Little else is recorded of Caesar’s childhood. Suetonius and Plutarch’s biographies of him both begin abruptly in Caesar’s teens; the opening paragraphs of both appear to be lost. Caesar’s formative years were a time of turmoil. The Social War was fought from 91 to 88 BC between Rome and her Italian allies over the issue of Roman citizenship, while Mithridates of Pontus threatened Rome’s eastern provinces. Domestically, Roman politics was divided between politicians known as optimates and populares. The optimates were conservative, defended the interests of the upper class and used and promoted the authority of the Senate; the populares advocated reform in the interests of the masses and used and promoted the authority of the Popular Assemblies. Caesar’s uncle Marius was a popularis , Marius’ protégé Lucius Cornelius Sulla was an optimas , and in Caesar’s youth their rivalry led to civil war. Both Marius and Sulla distinguished themselves in the Social War, and both wanted command of the war against Mithridates, which was initially given to Sulla; but when Sulla left the city to take command of his army, a tribune passed a law transferring the appointment to Marius. He and his ally Lucius Cornelius Cinna seized the city and declared Sulla a public enemy, and Marius’s troops took violent revenge on Sulla’s supporters. Marius died early in 86 BC, but his followers remained in power. In 85 BC Caesar’s father died suddenly while putting on his shoes one morning, without any apparent cause, and at sixteen, Caesar was the head of the family. The following year he was nominated to be the new Flamen Dialis , high priest of Jupiter, as Merula, the previous incumbent, had died in Marius’s purges. Since the holder of that position not only had to be a patrician but also be married to a patrician, he broke off his engagement to Cossutia, a plebeian girl of wealthy equestrian family he had been betrothed to since boyhood, and married Cinna’s daughter Cornelia. After a campaign throughout Italy he seized Rome at the Battle of the Colline Gate in November 82 BC and had himself appointed to the revived office of dictator; but whereas a dictator was traditionally appointed for six months at a time, Sulla’s appointment had no term limit. Statues of Marius were destroyed and Marius’ body was exhumed and thrown in the Tiber. Cinna was already dead, killed by his own soldiers in a mutiny. Sulla’s proscriptions saw hundreds of his political enemies killed or exiled. Caesar, as the nephew of Marius and son-in-law of Cinna, was targeted. He was stripped of his inheritance, his wife’s dowry and his priesthood, but he refused to divorce Cornelia and was forced to go into hiding. The threat against him was lifted by the intervention of his mother’s family, which included supporters of Sulla, and the Vestal Virgins. Sulla gave in reluctantly, and is said to have declared that he saw many a Marius in Caesar. Feeling it much safer to be far away from Sulla should the Dictator change his mind, Caesar quit Rome and joined the army, serving under Marcus Minucius Thermus in Asia and Servilius Isauricus in Cilicia. He served with distinction, winning the Civic Crown for his part in the siege of Mytilene. On a mission to Bithynia to secure the assistance of King Nicomedes’s fleet, he spent so long at his court that rumours of an affair with the king arose, which would persist for the rest of his life. Ironically, the loss of his priesthood had allowed him to pursue a military career: the Flamen Dialis was not permitted to touch a horse, sleep three nights outside his own bed or one night outside Rome, or look upon an army. At the end of 81 BC, Sulla resigned his dictatorship, re-established consular government and, after serving as consul in 80 BC, retired to private life. In a manner that the historian Suetonius thought arrogant, Julius Caesar would later mock Sulla for resigning the Dictatorship-“Sulla did not know his political ABC’s”. He died two years later in 78 BC and was accorded a state funeral. Hearing of Sulla’s death, Caesar felt safe enough to return to Rome. Lacking means since his inheritance was confiscated, he acquired a modest house in the Subura, a lower-class neighbourhood of Rome. His return coincided with an attempted anti-Sullan coup by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus but Caesar, lacking confidence in Lepidus’s leadership, did not participate. Instead he turned to legal advocacy. He became known for his exceptional oratory, accompanied by impassioned gestures and a high-pitched voice, and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption. Even Cicero praised him: Come now, what orator would you rank above him… ? Aiming at rhetorical perfection, Caesar travelled to Rhodes in 75 BC to study under Apollonius Molon, who had previously taught Cicero. On the way across the Aegean Sea, Caesar was kidnapped by Cilician (not to be confused with Sicilian) pirates and held prisoner in the Dodecanese islet of Pharmacusa. He maintained an attitude of superiority throughout his captivity. When the pirates thought to demand a ransom of twenty talents of silver, he insisted they ask for fifty. After the ransom was paid, Caesar raised a fleet, pursued and captured the pirates, and imprisoned them in Pergamon. As a sign of leniency, he first had their throats cut. He then proceeded to Rhodes, but was soon called back into military action in Asia, raising a band of auxiliaries to repel an incursion from Pontus. On his return to Rome he was elected military tribune, a first step on the cursus honorum of Roman politics. The war against Spartacus took place around this time (73-71 BC), but it is not recorded what role, if any, Caesar played in it. He was elected quaestor for 69 BC, and during that year he delivered the funeral oration for his aunt Julia, widow of Marius, and included images of Marius, unseen since the days of Sulla, in the funeral procession. His own wife Cornelia also died that year. After her funeral, in the spring or early summer of 69 BC, Caesar went to serve his quaestorship in Hispania under Antistius Vetus. While there he is said to have encountered a statue of Alexander the Great, and realised with dissatisfaction he was now at an age when Alexander had the world at his feet, while he had achieved comparatively little. On his return in 67 BC, he married Pompeia, a granddaughter of Sulla. He was elected aedile and restored the trophies of Marius’s victories; a controversial move given the Sullan regime was still in place. He was also suspected of involvement in two abortive coup attempts. 63 BC was an eventful year for Caesar. He persuaded a tribune, Titus Labienus, to prosecute the optimate senator Gaius Rabirius for the political murder, 37 years previously, of the tribune Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, and had himself appointed as one of the two judges to try the case. Rabirius was defended by both Cicero and Quintus Hortensius, but was convicted of perduellio (treason). While he was exercising his right of appeal to the people, the praetor Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer adjourned the assembly by taking down the military flag from the Janiculum hill. Labienus could have resumed the prosecution at a later session, but did not do so: Caesar’s point had been made, and the matter was allowed to drop. Labienus would remain an important ally of Caesar over the next decade. The same year, Caesar ran for election to the post of Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the Roman state religion, after the death of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, who had been appointed to the post by Sulla. He ran against two powerful optimates , the former consuls Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus. There were accusations of bribery by all sides. Caesar is said to have told his mother on the morning of the election that he would return as Pontifex Maximus or not at all, expecting to be forced into exile by the enormous debts he had run up to fund his campaign. In any event he won comfortably, despite his opponents’ greater experience and standing, possibly because the two older men split their votes. The post came with an official residence on the Via Sacra. When Cicero, who was consul that year, exposed Catiline’s conspiracy to seize control of the republic, Catulus and others accused Caesar of involvement in the plot. Caesar, who had been elected praetor for the following year, took part in the debate in the Senate on how to deal with the conspirators. During the debate, Caesar was passed a note. Marcus Porcius Cato, who would become his most implacable political opponent, accused him of corresponding with the conspirators, and demanded that the message be read aloud. Caesar passed him the note, which, embarrassingly, turned out to be a love letter from Cato’s half-sister Servilia. Caesar argued persuasively against the death penalty for the conspirators, proposing life imprisonment instead, but a speech by Cato proved decisive, and the conspirators were executed. The following year a commission was set up to investigate the conspiracy, and Caesar was again accused of complicity. On Cicero’s evidence that he had reported what he knew of the plot voluntarily, however, he was cleared, and one of his accusers, and also one of the commissioners, were sent to prison. While praetor in 62 BC, Caesar supported Metellus Celer, now tribune, in proposing controversial legislation, and the pair were so obstinate they were suspended from office by the Senate. The Senate was persuaded to reinstate him after he quelled public demonstrations in his favour. That year the festival of the Bona Dea (“good goddess”) was held at Caesar’s house. No men were permitted to attend, but a young patrician named Publius Clodius Pulcher managed to gain admittance disguised as a woman, apparently for the purpose of seducing Caesar’s wife Pompeia. He was caught and prosecuted for sacrilege. Caesar gave no evidence against Clodius at his trial, careful not to offend one of the most powerful patrician families of Rome, and Clodius was acquitted after rampant bribery and intimidation. Nevertheless, Caesar divorced Pompeia, saying that my wife ought not even to be under suspicion. After his praetorship, Caesar was appointed to govern Hispania Ulterior (Outer Iberia), but he was still in considerable debt and needed to satisfy his creditors before he could leave. He turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome’s richest men. In return for political support in his opposition to the interests of Pompey, Crassus paid some of Caesar’s debts and acted as guarantor for others. Even so, to avoid becoming a private citizen and open to prosecution for his debts, Caesar left for his province before his praetorship had ended. In Hispania he conquered the Callaici and Lusitani, being hailed as imperator by his troops, reformed the law regarding debts, and completed his governorship in high esteem. Being hailed as imperator entitled Caesar to a triumph. However, he also wanted to stand for consul, the most senior magistracy in the republic. If he were to celebrate a triumph, he would have to remain a soldier and stay outside the city until the ceremony, but to stand for election he would need to lay down his command and enter Rome as a private citizen. He could not do both in the time available. He asked the senate for permission to stand in absentia , but Cato blocked the proposal. Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship. First consulship and triumvirate. Three candidates stood for the consulship: Caesar, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, who had been aedile with Caesar several years earlier, and Lucius Lucceius. The election was dirty. Caesar canvassed Cicero for support, and made an alliance with the wealthy Lucceius, but the establishment threw its financial weight behind the conservative Bibulus, and even Cato, with his reputation for incorruptibility, is said to have resorted to bribery in his favour. Caesar and Bibulus were elected as consuls for 59 BC. Caesar was already in Crassus’s political debt, but he also made overtures to Pompey, who was unsuccessfully fighting the Senate for ratification of his eastern settlements and farmland for his veterans. Pompey and Crassus had been at odds since they were consuls together in 70 BC, and Caesar knew if he allied himself with one he would lose the support of the other, so he endeavoured to reconcile them. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate (rule of three men), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar’s daughter Julia. Caesar also married again, this time Calpurnia, daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, who was elected to the consulship for the following year. Caesar proposed a law for the redistribution of public lands to the poor, a proposal supported by Pompey, by force of arms if need be, and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, and the triumvirate’s opponents were intimidated. Bibulus attempted to declare the omens unfavourable and thus void the new law, but was driven from the forum by Caesar’s armed supporters. His lictors had their fasces broken, two tribunes accompanying him were wounded, and Bibulus himself had a bucket of excrement thrown over him. In fear of his life, he retired to his house for the rest of the year, issuing occasional proclamations of bad omens. These attempts to obstruct Caesar’s legislation proved ineffective. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as “the consulship of Julius and Caesar”. This also gave rise to this lampoon. The event occurred, as I recall, when Caesar governed Rome. Caesar, not Bibulus, who kept his seat at home. With the help of Piso and Pompey, Caesar later had this overturned, and was instead appointed to govern Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy) and Illyricum (the western Balkans), with Transalpine Gaul (southern France) later added, giving him command of four legions. The term of his proconsulship, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the usual one. When his consulship ended, Caesar narrowly avoided prosecution for the irregularities of his year in office, and quickly left for his province. Caesar had four legions under his command, two of his provinces, Illyricum and Gallia Narbonensis, bordered on unconquered territory, and independent Gaul was known to be unstable. Rome’s allies the Aedui had been defeated by their Gallic rivals, with the help of a contingent of Germanic Suebi under Ariovistus, who had settled in conquered Aeduan land, and the Helvetii were mobilising for a mass migration, which the Romans feared had warlike intent. Caesar raised two new legions and defeated first the Helvetii, then Ariovistus, and left his army in winter quarters in the territory of the Sequani, signaling that his interest in the lands outside Gallia Narbonensis would not be temporary. He began his second year with double the military strength he had begun with, having raised another two legions in Cisalpine Gaul during the winter. The legality of this was dubious, as the Cisalpine Gauls were not Roman citizens. In response to Caesar’s activities the previous year, the Belgic tribes of north-eastern Gaul had begun to arm themselves. Caesar treated this as an aggressive move, and, after an inconclusive engagement against a united Belgic army, conquered the tribes piecemeal. Meanwhile, one legion, commanded by Crassus’ son Publius, began the conquest of the tribes of the Armorican peninsula. During the spring of 56 BC the Triumvirate held a conference at Luca (modern Lucca) in Cisalpine Gaul. Rome was in turmoil, and Clodius’ populist campaigns had been undermining relations between Crassus and Pompey. The meeting renewed the Triumvirate and extended Caesar’s proconsulship for another five years. Crassus and Pompey would be consuls again, with similarly long-term proconsulships to follow: Syria for Crassus, the Hispanian provinces for Pompey. The conquest of Armorica was completed when Caesar defeated the Veneti in a naval battle, while young Crassus conquered the Aquitani of the south-west. By the end of campaigning in 56 BC only the Morini and Menapii of the coastal Low Countries still held out. In 55 BC Caesar repelled an incursion into Gaul by the Germanic Usipetes and Tencteri, and followed it up by building a bridge across the Rhine and making a show of force in Germanic territory, before returning and dismantling the bridge. Late that summer, having subdued the Morini and Menapii, he crossed to Britain, claiming that the Britons had aided the Veneti against him the previous year. He advanced inland, establishing Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as a friendly king and bringing his rival, Cassivellaunus, to terms. But poor harvests led to widespread revolt in Gaul, led by Ambiorix of the Eburones, forcing Caesar to campaign through the winter and into the following year. With the defeat of Ambiorix, Caesar believed Gaul was now pacified. While Caesar was in Britain his daughter Julia, Pompey’s wife, had died in childbirth. Caesar tried to resecure Pompey’s support by offering him his great-niece Octavia in marriage, alienating Octavia’s husband Gaius Marcellus, but Pompey declined. In 53 BC Crassus was killed leading a failed invasion of Parthia. Rome was on the edge of violence. Pompey was appointed sole consul as an emergency measure, and married Cornelia, daughter of Caesar’s political opponent Quintus Metellus Scipio, whom he invited to become his consular colleague once order was restored. The Triumvirate was dead. In 52 BC another, larger revolt erupted in Gaul, led by Vercingetorix of the Arverni. Vercingetorix managed to unite the Gallic tribes and proved an astute commander, defeating Caesar in several engagements including the Battle of Gergovia, but Caesar’s elaborate siege-works at the Battle of Alesia finally forced his surrender. Despite scattered outbreaks of warfare the following year, Gaul was effectively conquered. Titus Labienus was Caesar’s most senior legate during his Gallic campaigns, having the status of propraetor. Other prominent men who served under him included his relative Lucius Julius Caesar, Crassus’ sons Publius and Marcus, Cicero’s brother Quintus, Decimus Brutus, and Mark Antony. Plutarch claimed that the army had fought against three million men in the course of the Gallic Wars, of whom 1 million died, and another million were enslaved. 300 tribes were subjugated and 800 cities were destroyed. Almost the entire population of the city of Avaricum (Bourges) (40,000 in all) was slaughtered. However, in view of the difficulty of finding accurate counts in the first place, Caesar’s propagandistic purposes, and the common gross exaggeration of numbers in ancient texts, the totals of enemy combatants in particular are likely to be far too high. Furger-Gunti considers an army of more than 60,000 fighting Helvetii extremely unlikely in the view of the tactics described, and assumes the actual numbers to have been around 40,000 warriors out of a total of 160,000 emigrants. Delbrück suggests an even lower number of 100,000 people, out of which only 16,000 were fighters, which would make the Celtic force about half the size of the Roman body of ca. In 50 BC, the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome because his term as Proconsul had finished. Moreover, the Senate forbade Caesar to stand for a second consulship in absentia. Caesar thought he would be prosecuted and politically marginalised if he entered Rome without the immunity enjoyed by a Consul or without the power of his army. Pompey accused Caesar of insubordination and treason. On 10 January 49 BC Caesar crossed the Rubicon river (the frontier boundary of Italy) with only one legion and ignited civil war. Upon crossing the Rubicon, Plutarch reports that Caesar quoted the Athenian playwright Menander in Greek, saying (let the dice be tossed). Suetonius gives the Latin approximation alea iacta est (the die is tossed). The Optimates, including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger, fled to the south, having little confidence in the newly raised troops especially since so many cities in northern Italy had voluntarily surrendered. An attempted stand by a consulate legion in Samarium resulted in the consul being handed over by the defenders and the legion surrendering without significant fighting. Despite greatly outnumbering Caesar, who only had his Thirteenth Legion with him, Pompey had no intention of fighting. Caesar pursued Pompey to Brindisium, hoping to capture Pompey before the trapped Senate and their legions could escape. Pompey managed to elude him, sailing out of the harbour before Caesar could break the barricades. Lacking a naval force since Pompey had already scoured the coasts of all ships for evacuation of his forces, Caesar decided to head for Hispania saying I set forth to fight an army without a leader, so as later to fight a leader without an army. Leaving Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as prefect of Rome, and the rest of Italy under Mark Antony as tribune, Caesar made an astonishing 27-day route-march to Hispania, rejoining two of his Gallic legions, where he defeated Pompey’s lieutenants. He decisively defeated Pompey, despite Pompey’s numerical advantage (nearly twice the number of infantry and considerably more cavalry), at Pharsalus in an exceedingly short engagement in 48 BC. In Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator, with Mark Antony as his Master of the Horse; Caesar presided over his own election to a second consulate (with Publius Servilius Vatia as his colleague) and then, after eleven days, resigned this dictatorate. Cleopatra Before Caesar by the artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1866. He pursued Pompey to Alexandria, where Pompey was murdered by a former Roman officer serving in the court of King Ptolemy XIII. Caesar then became involved with the Alexandrine civil war between Ptolemy and his sister, wife, and co-regent queen, the Pharaoh Cleopatra VII. Perhaps as a result of Ptolemy’s role in Pompey’s murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra; he is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey’s head, which was offered to him by Ptolemy’s chamberlain Pothinus as a gift. In any event, Caesar defeated the Ptolemaic forces in 47 BC in the Battle of the Nile and installed Cleopatra as ruler. Caesar and Cleopatra celebrated their victory of the Alexandrine civil war with a triumphant procession on the Nile in the spring of 47 B. The royal barge was accompanied by 400 additional ships, introducing Caesar to the luxurious lifestyle of the Egyptian pharaohs. Caesar and Cleopatra never married, as Roman Law only recognised marriages between two Roman citizens. Caesar continued his relationship with Cleopatra throughout his last marriage, which lasted 14 years – in Roman eyes, this did not constitute adultery – and may have fathered a son called Caesarion. Cleopatra visited Rome on more than one occasion, residing in Caesar’s villa just outside Rome across the Tiber. Late in 48 BC, Caesar was again appointed Dictator, with a term of one year. After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, Caesar went to the Middle East, where he annihilated King Pharnaces II of Pontus in the Battle of Zela; his victory was so swift and complete that he mocked Pompey’s previous victories over such poor enemies. Thence, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey’s senatorial supporters. He quickly gained a significant victory at Thapsus in 46 BC over the forces of Metellus Scipio (who died in the battle) and Cato the Younger (who committed suicide). After this victory, he was appointed Dictator for ten years. Nevertheless, Pompey’s sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus, Caesar’s former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore) and second in command in the Gallic War, escaped to Hispania. Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Battle of Munda in March 45 BC. During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) and 45 BC (without colleague). Aftermath of the civil war. While he was still campaigning in Hispania, the Senate began bestowing honours on Caesar in absentia. Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoning almost all, and there was no serious public opposition to him. Great games and celebrations were held on 21 April to honour Caesar’s victory at Munda. Plutarch writes that many Romans found the triumph held following Caesar’s victory to be in poor taste, as those defeated in the civil war had not been foreigners, but instead fellow Romans. On Caesar’s return to Italy in September 45 BC, he filed his will, naming his grandnephew Gaius Octavius (Octavian) as the heir to everything, including his name. Caesar also wrote that if Octavian died before Caesar did, Marcus Junius Brutus would be the next heir in succession. From 47 to 44 he made plans for the distribution of land to about 15,000 of his veterans. In 63 BC Caesar had been elected Pontifex Maximus, and one of his roles as such was settling the calendar. A complete overhaul of the old Roman calendar proved to be one of his most long lasting and influential reforms. In 46 BC, Caesar established a 365-day year with a leap year every fourth year. This Julian calendar was subsequently modified by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 into the modern Gregorian calendar. As a result of this reform, a certain Roman year (mostly equivalent to 46 BC in the modern calendar) was made 445 days long, to bring the calendar into line with the seasons. The month of July is named after Julius in his honour. The Forum of Caesar, with its Temple of Venus Genetrix, was built among many other public works. On the Ides of March (15 March; see Roman calendar) of 44 BC, Caesar was due to appear at a session of the Senate. Mark Antony, having vaguely learned of the plot the night before from a terrified Liberator named Servilius Casca, and fearing the worst, went to head Caesar off. The plotters, however, had anticipated this and, fearing that Antony would come to Caesar’s aid, had arranged for Trebonius to intercept him just as he approached the portico of Theatre of Pompey, where the session was to be held, and detain him outside. Plutarch, however, assigns this action to delay Antony to Brutus Albinus. When he heard the commotion from the senate chamber, Antony fled. The senators encircle Caesar. According to Plutarch, as Caesar arrived at the Senate Tillius Cimber presented him with a petition to recall his exiled brother. The other conspirators crowded round to offer support. Both Plutarch and Suetonius say that Caesar waved him away, but Cimber grabbed his shoulders and pulled down Caesar’s tunic. Caesar then cried to Cimber, Why, this is violence! ” ” Ista quidem vis est! At the same time, Casca produced his dagger and made a glancing thrust at the dictator’s neck. Caesar turned around quickly and caught Casca by the arm. According to Plutarch, he said in Latin, Casca, you villain, what are you doing? ” Casca, frightened, shouted “Help, brother! Within moments, the entire group, including Brutus, was striking out at the dictator. Caesar attempted to get away, but, blinded by blood, he tripped and fell; the men continued stabbing him as he lay defenceless on the lower steps of the portico. According to Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination. He was stabbed 23 times. According to Suetonius, a physician later established that only one wound, the second one to his chest, had been lethal. The dictator’s last words are not known with certainty, and are a contested subject among scholars and historians alike. Suetonius reports that others have said Caesar’s last words were the Greek phrase ” , ;”transliterated as Kai su, teknon? However, Suetonius himself says Caesar said nothing. Plutarch also reports that Caesar said nothing, pulling his toga over his head when he saw Brutus among the conspirators. The version best known in the English-speaking world is the Latin phrase Et tu, Brute? “, commonly rendered as “You too, Brutus? “; this derives from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar , where it actually forms the first half of a macaronic line: ” Et tu, Brute? It has no basis in historical fact and Shakespeare’s use of Latin here is not from any assertion that Caesar would have been using the language, rather than the Greek reported by Suetonius, but because the phrase was already popular at the time the play was written. According to Plutarch, after the assassination, Brutus stepped forward as if to say something to his fellow senators; they, however, fled the building. Brutus and his companions then marched to the Capitol while crying out to their beloved city: People of Rome, we are once again free! They were met with silence, as the citizens of Rome had locked themselves inside their houses as soon as the rumour of what had taken place had begun to spread. A wax statue of Caesar was erected in the forum displaying the 23 stab wounds. A crowd who had amassed there started a fire, which badly damaged the forum and neighbouring buildings. In the ensuing chaos Mark Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), and others fought a series of five civil wars, which would end in the formation of the Roman Empire. Aftermath of the assassination. The result unforeseen by the assassins was that Caesar’s death precipitated the end of the Roman Republic. The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular and had been since before Gaul, became enraged that a small group of high-browed aristocrats had killed their champion. Antony, who had been drifting apart from Caesar, capitalised on the grief of the Roman mob and threatened to unleash them on the Optimates, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself. But, to his surprise and chagrin, Caesar had named his grandnephew Gaius Octavian his sole heir, bequeathing him the immensely potent Caesar name as well as making him one of the wealthiest citizens in the Republic. The crowd at the funeral boiled over, throwing dry branches, furniture and even clothing on to Caesar’s funeral pyre, causing the flames to spin out of control, seriously damaging the Forum. The mob then attacked the houses of Brutus and Cassius, where they were repelled only with considerable difficulty, ultimately providing the spark for the Liberators’ civil war, fulfilling at least in part Antony’s threat against the aristocrats. However, Antony did not foresee the ultimate outcome of the next series of civil wars, particularly with regard to Caesar’s adopted heir. Octavian, aged only 18 at the time of Caesar’s death, proved to have considerable political skills, and while Antony dealt with Decimus Brutus in the first round of the new civil wars, Octavian consolidated his tenuous position. In order to combat Brutus and Cassius, who were massing an enormous army in Greece, Antony needed soldiers, the cash from Caesar’s war chests, and the legitimacy that Caesar’s name would provide for any action he took against them. With the passage of the lex Titia on 27 November 43 BC, the Second Triumvirate was officially formed, composed of Antony, Octavian, and Caesar’s loyal cavalry commander Lepidus. It formally deified Caesar as Divus Iulius in 42 BC, and Caesar Octavian henceforth became Divi filius (“Son of a god”). Seeing that Caesar’s clemency had resulted in his murder, the Second Triumvirate brought back the horror of proscription, abandoned since Sulla. It engaged in the legally-sanctioned murder of a large number of its opponents in order to secure funding for its forty-five legions in the second civil war against Brutus and Cassius. Antony and Octavius defeated them at Philippi. Afterward, Mark Antony married Caesar’s lover, Cleopatra, intending to use the fabulously wealthy Egypt as a base to dominate Rome. A third civil war broke out between Octavian on one hand and Antony and Cleopatra on the other. This final civil war, culminating in the latter’s defeat at Actium, resulted in the permanent ascendancy of Octavian, who became the first Roman emperor, under the name Caesar Augustus, a name that raised him to status of a deity. Julius Caesar had been preparing to invade Parthia, the Caucasus and Scythia, and then swing back onto Germania through Eastern Europe. These plans were thwarted by his assassination. His successors did attempt the conquests of Parthia and Germania, but without lasting results. Based on remarks by Plutarch, Caesar is sometimes thought to have suffered from epilepsy. Modern scholarship is “sharply divided” on the subject, and it is more certain that he was plagued by malaria, particularly during the Sullan proscriptions of the 80s. Caesar had four documented episodes of what may have been complex partial seizures. He may additionally have had absence seizures in his youth. The earliest accounts of these seizures were made by the biographer Suetonius who was born after Caesar died. The claim of epilepsy is countered among some medical historians by a claim of hypoglycemia, which can cause epileptoid seizures. Caesar was considered during his lifetime to be one of the best orators and authors of prose in Rome-even Cicero spoke highly of Caesar’s rhetoric and style. Among his most famous works were his funeral oration for his paternal aunt Julia and his Anticato , a document written to blacken Cato’s reputation and respond to Cicero’s Cato memorial. Poems by Caesar are also mentioned in ancient sources. His works other than his war commentaries and his speeches have been lost. The Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), campaigns in Gallia and Britannia during his term as proconsul; and. The Commentarii de Bello Civili (Commentaries on the Civil War), events of the Civil War until immediately after Pompey’s death in Egypt. Other works historically attributed to Caesar, but whose authorship is doubted, are. De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria. De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa; and. De Bello Hispaniensi (On the Hispanic War), campaigns in the Iberian peninsula. These narratives were written and published on a yearly basis during or just after the actual campaigns, as a sort of “dispatches from the front”. Apparently simple and direct in style-to the point that Caesar’s Commentarii are commonly studied by first and second year Latin students-they are in fact highly sophisticated tracts, aimed most particularly at the middle-brow readership of minor aristocrats in Rome, Italy, and the provinces. Using the Latin alphabet as it existed in the day of Caesar i. Without lower case letters, “J”, or “U”, Caesar’s name is properly rendered “GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR”. The form “CAIVS” is also attested using the old Roman pronunciation of letter C as G; it is an antique form of the more common “GAIVS”. It is often seen abbreviated to C. The letterform “Æ” is a ligature, which is often encountered in Latin inscriptions where it was used to save space, and is nothing more than the letters “ae”. In Classical Latin, it was pronounced [aius julius kaisar]. In the days of the late Roman Republic, many historical writings were done in Greek, a language most educated Romans studied. Young wealthy Roman boys were often taught by Greek slaves and sometimes sent to Athens for advanced training, as was Caesar’s principal assassin, Brutus. In Greek, during Caesar’s time, his family name was written , reflecting its contemporary pronunciation. Thus his name is pronounced in a similar way to the pronunciation of the German Kaiser. This German name was phonemically but not phonetically derived from the Middle Ages Ecclesiastical Latin, in which the familiar part “Caesar” is [tesar], from which the modern English pronunciation is derived, as well as the title of Tsar. His name is also remembered in Norse mythology, where he is manifested as the legendary king Kjárr. World-renowned expert numismatist, enthusiast, author and dealer in authentic ancient Greek, ancient Roman, ancient Byzantine, world coins & more. Ilya Zlobin is an independent individual who has a passion for coin collecting, research and understanding the importance of the historical context and significance all coins and objects represent. Send me a message about this and I can update your invoice should you want this method. Getting your order to you, quickly and securely is a top priority and is taken seriously here. Great care is taken in packaging and mailing every item securely and quickly. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Additionally, the coin is inside it’s own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2×2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. Whether your goal is to collect or give the item as a gift, coins presented like this could be more prized and valued higher than items that were not given such care and attention to. When should I leave feedback? Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens sometimes that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for their order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. How and where do I learn more about collecting ancient coins? Visit the Guide on How to Use My Store. For on an overview about using my store, with additional information and links to all other parts of my store which may include educational information on topics you are looking for. The item “JULIUS CAESAR Authentic Ancient 49BC Silver Coin w ELEPHANT NGC Certified i69582″ is in sale since Saturday, May 12, 2018. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ Ancient\Roman\ Republic (300 BC-27 BC)”. The seller is “highrating_lowprice” and is located in Rego Park, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Composition: Silver

- Culture: Roman

- Material: Silver

- Certification: NGC

- Denomination: Denarius

- Grade: Ch AU

- Certification Number: 4625702-001