Monthly Archives: April 2018

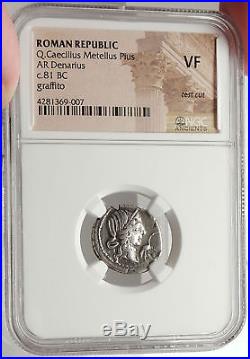

SULLA’s General as IMPERATOR 81BC Silver Roman Republic Coin ELEPHANT NGC i67613

Item: i67613 Authentic Ancient Coin of. Caecilius Metellus Pius as Imperator Silver Denarius 20mm (3.56 grams) Spain mint: 81 B. 374/1 Certification: NGC Ancients. VF 4281369-007 Diademed head of Pietas right, stork before. Elephant walking left, Q. Metellus received the title of Pius when he besought the Roman people to bring his father back from banishment and therefore on the obverse you have Pietas (Piety) goddess. Metellus Pius became Imperator while campaigning for Sulla. Sulla was dictator circa 82-81 B. Metellus became Pontifex Maximus in 81 B. After Pompey’s defeat by Caesar at Pharsalus (Greece) in 48 and then his subsequent murder, his followers gathered in Africa and several of them struck coinage on their own account. One of them was Metellus Scipio who produced five issues; one alone, three others with the legate Junianus as here and the fifth with M. It is uncertain whether his use of IMP on all of them indicated that he had actually been hailed as imperator by his troops or was meant to justify his coinage. It was Metellus Scipio who disclosed to Cicero the Cataline conspiracy, was consul with Pompey in 52, and governor of Selucia in 49. He commanded the center line of Pompey’s army at Pharsalus, after which he fled to Africa and formed an alliance with Juba, King of Numidia. Metellus Scipio was a Cornelius Scipio who was adopted into the Caecilius clan and was therefore related to Scipio Africanus who defeated Hannibal at Zama in 202 and won the Second Punic War. He appeared to believe that the cognomen Scipio (scepter) held some power. All of his coinage, filled with symbols of hoped-for victory, is pathetically true to its author’s belief in the’ felix et invictum Scipionum nomen’ (per Seutonius:’the good luck and invincibility of the name Scipio’). This belief was overcome by the greater felicitas of Caesar, who defeated him at Thapsus (Tunisia) in B. Or read the Guide to the Coins of the Roman Republic. Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica c. 100/98 BC – 46 BC, in modern scholarship often as Metellus Scipio , was a Roman consul and military commander in the Late Republic. During the civil war between Julius Caesar and the senatorial faction led by Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”), he remained a staunch optimate. He led troops against Caesar’s forces, mainly in the battles of Pharsalus and Thapsus, where he was defeated. He later committed suicide. Ronald Syme called him the last Scipio of any consequence in Roman history. Family connections and name. Metellus Scipio was born Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica. His grandfather was the P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio who was consul in 111 BC; his father married Licinia Crassa, daughter of the L. Licinius Crassus who was consul in 95 BC. The father died not long after his praetorship c. 93 BC, and was survived by two sons and two daughters. The brother was adopted by their grandfather Crassus, but left little mark on history. Publius Scipio, as he was referred to in contemporary sources early in his life, was adopted in adulthood through the testament of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, consul in 80 BC and pontifex maximus. He retained his patrician status: “Scipio’s ancestry, ” notes Syme, was unmatched for splendour. ” As Jerzy Linderski has shown at length, this legal process constitutes adoption only in a loose sense; Scipio becomes a Caecilius Metellus in name while inheriting the estate of Metellus Pius, but was never his “son while the pontifex maximus was alive. He was called “Metellus Scipio” but also sometimes just “Scipio” even after his adoption. The official form of his name as evidenced in a decree of the senate was Q. Scipio married Aemilia Lepida, daughter of Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus Livianus (consul 77 BC), but was not without rival in the match. The virginal Cato had also wanted to marry Aemilia and lost out in the seduction. When [Cato] thought that he was old enough to marry, – and up to that time he had consorted with no woman, – he engaged himself to Lepida, who had formerly been betrothed to Metellus Scipio, but was now free, since Scipio had rejected her and the betrothal had been broken. However, before the marriage Scipio changed his mind again, and by dint of every effort got the maid. Cato was greatly exasperated and inflamed by this, and attempted to go to law about it; but his friends prevented this, and so, in his rage and youthful fervour, he betook himself to iambic verse, and heaped much scornful abuse upon Scipio… The couple had one son, a Metellus Scipio who seems to have died when he was only 18. Another son may have been born around 70, or a son may have been adopted. The couple’s much more famous daughter was born around that time as well. Scipio first married off the celebrated Cornelia Metella to Publius Crassus, the son of Marcus Licinius Crassus. After Publius’s premature death at Carrhae, Scipio decided to succeed Caesar as the father-in-law of Pompeius, who was at least thirty years older than Cornelia. The marriage is one of the acts by which Pompeius severed his alliance to Caesar and declared himself the champion of the optimates. He and Scipio were consuls together in 52. Scipio among the young nobiles on his defense team when Roscius of Ameria [sic] was prosecuted in 80 BC. He is placed in the company of M. Messalla and Metellus Celer, both future consuls. Metellus Scipio has been listed as tribune of the plebs in 59, but his patrician status argues against his holding the office. It is possible that Scipio’s’adoption’ into a plebeian gens may have qualified him for a tribunate on a technicality. He was possibly curule aedile in 57 BC, when he presented funeral games in honor of his adopted father’s death six years earlier. He was praetor, most likely in 55 BC, during the second joint consulship of Pompeius and Marcus Crassus. In 53 BC, he was interrex with M. He became consul with Pompeius in 52 BC, the year he arranged the marriage of his newly widowed daughter to him. Indisputably aristocratic and conservative, Metellus Scipio had been at least symbolically a counterweight to the power of the so-called triumvirate before the death of Crassus in 53. “Opportune deaths, ” notes Syme, had enhanced his value, none remaining now of the Metellan consuls. He is known to have been a member of the College of Pontiffs by 57 BC, and was probably nominated upon the death of his adoptive father in 63 and subsequently elected. Role in civil war. In January 49 BC, Metellus Scipio persuaded the senate to issue the ultimatum to Caesar that made war inevitable. That same year, he became proconsul of the province of Syria. Scipio put to death Alexander of Judaea, and was acclaimed Imperator for “alleged” victories in the Amanus Mountains – as noted disparagingly by Caesar. In 48 BC, he brought his forces from Asia to Greece, where he maneuvered against Gn. Domitius Calvinus and L. Cassius until the arrival of Pompeius. At the Battle of Pharsalus, he commanded the center. After the optimates’ defeat by Caesar, Metellus fled to Africa. With the support of his former rival-in-romance Cato, he wrested the chief command of Pompeius’s forces from the loyal Attius Varus, probably in early 47. In 46 BC, he held command at the Battle of Thapsus “without skill or success, ” and was defeated along with Cato. After the defeat he tried to escape to the Iberian Peninsula to continue the fight, but was cornered by the fleet of Publius Sittius. He committed suicide by stabbing himself so he would not fall at the hands of his enemies. Facing death, Metellus Scipio achieved an uncharacteristic dignity, famously departing from his soldiers with a nonchalant Imperator se bene habet (“Your general’s just fine”). These last words elicited strong praise from the Stoic moral philosopher Seneca. He therefore pierced his body with a sword; and when they asked where the commander was, he replied:’All is well with the commander. These words brought him up to the level of his ancestors and suffered not the glory which fate gave to the Scipios in Africa to lose its continuity. It was a great deed to conquer Carthage, but a greater deed to conquer death. All is well with the commander! Ought a general to die otherwise, especially one of Cato’s generals? Classical scholar John H. Collins summed up the character and reputation of Metellus Scipio. From all that can be learned of this Scipio, he was as personally despicable and as politically reactionary as they come: a defender of C. 79-81, a debauchee of singular repulsiveness (Valerius Maximus, 9.1.8), an incompetent and bull-headed commander Plutarch, Cato Min. 58, an undisciplined tyrant in the possession of authority Bell. 44-46, an extortioner of the provinces (BC 3.31-33), a proscription-thirsty bankrupt Att. , a worthy great grandson des hochmütigen, plebejerfeindlichen Junkers (Münzer, RE 4.1502) who had led the lynching of Tiberius Gracchus, and a most unworthy father of the gentle Cornelia. Only in the Imperator se bene habet with which he met death is there any trace of the nobler character of his great forebears Seneca Rhet. Caesar’s civil war. The Roman Republic (Latin: Res Publica Romana) was the period of the ancient Roman civilization when the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 509 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and advised by a senate. A complex constitution gradually developed, centered on the principles of a separation of powers and checks and balances. Except in times of dire national emergency, public offices were limited to one year, so that, in theory at least, no single individual could dominate his fellow citizens. Roman provinces on the eve of the assassination of Julius Caesar, 44 BC. Roman society was hierarchical. The evolution of the Constitution of the Roman Republic was heavily influenced by the struggle between the patricians, Rome’s land-holding aristocracy, who traced their ancestry back to the early history of the Roman kingdom, and the plebeians, the far more numerous citizen-commoners. Over time, the laws that gave patricians exclusive rights to Rome’s highest offices were repealed or weakened, and a new aristocracy emerged from among the plebeian class. The leaders of the Republic developed a strong tradition and morality requiring public service and patronage in peace and war, making military and political success inextricably linked. During the first two centuries of its existence the Republic expanded through a combination of conquest and alliance, from central Italy to the entire Italian peninsula. By the following century it included North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Greece, and what is now southern France. Two centuries after that, towards the end of the 1st century BC, it included the rest of modern France, and much of the eastern Mediterranean. By this time, despite the Republic’s traditional and lawful constraints against any individual’s acquisition of permanent political powers, Roman politics was dominated by a small number of Roman leaders, their uneasy alliances punctuated by a series of civil wars. The victor in one of these civil wars, Octavian, reformed the Republic as a Principate, with himself as Rome’s “first citizen” (princeps). The Senate continued to sit and debate. Annual magistrates were elected as before, but final decisions on matters of policy, warfare, diplomacy and appointments were privileged to the princeps as “first among equals” later to be known as imperator due to the holding of imperium, from which the term emperor is derived. His powers were monarchic in all but name, and he held them for his lifetime, on behalf of the Senate and people of Rome. The Roman Republic was never restored, but neither was it abolished, so the exact date of the transition to the Roman Empire is a matter of interpretation. Historians have variously proposed the appointment of Julius Caesar as perpetual dictator in 44 BC, the defeat of Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and the Roman Senate’s grant of extraordinary powers to Octavian under the first settlement and his adopting the title Augustus in 27 BC, as the defining event ending the Republic. Many of Rome’s legal and legislative structures can still be observed throughout Europe and much of the world in modern nation states and international organizations. Latin, the language of the Romans, has influenced language across parts of Europe and the world. The Constitution of the Roman Republic was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The Roman constitution was not formal or even official. It was largely unwritten, uncodified, and constantly evolving. The Roman Forum, the commercial, cultural, and political center of the city and the Republic which housed the various offices and meeting places of the government. Senate of the Roman Republic. The Senate’s ultimate authority derived from the esteem and prestige of the Senate. This esteem and prestige was based on both precedent and custom, as well as the high calibre and prestige of the Senators. The Senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consulta. This was officially “advice” from the Senate to a magistrate. In practice, however, these were usually obeyed by the magistrates. The focus of the Roman Senate was directed towards foreign policy. Though it technically had no official role in the management of military conflict, the Senate ultimately was the force that oversaw such affairs. Not all those rights were available to every citizen – women could be citizens, but were denied the rights to vote or hold elected office. An adult male citizen with the full complement of legal and political rights was called optimo jure. The optimo jure elected their assemblies, whereupon the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies. The first was the comitia (“committees”), which were assemblies of all optimo jure. The second was the concilia (“councils”), which were assemblies of specific groups of optimo jure. Assembly of the Centuries. Citizens were organized on the basis of centuries and tribes. The centuries and the tribes would each gather into their own assemblies. The Comitia Centuriata (“Century Assembly”) was the assembly of the centuries. The president of the Comitia Centuriata was usually a consul. The centuries would vote, one at a time, until a measure received support from a majority of the centuries. The Comitia Centuriata would elect magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). It also elected censors. Only the Comitia Centuriata could declare war, and ratify the results of a census. It also served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases. Assembly of the Tribes. The assembly of the tribes, the Comitia Tributa, was presided over by a consul, and was composed of 35 tribes. The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical subdivisions. The order that the thirty-five tribes would vote in was selected randomly by lot. Once a measure received support from a majority of the tribes, the voting would end. While it did not pass many laws, the Comitia Tributa did elect quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes. The Plebeian Council was an assembly of plebeians, the non-patrician citizens of Rome, who would gather into their respective tribes. They elected their own officers, plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles. Usually a plebeian tribune would preside over the assembly. This assembly passed most laws, and could also act as a court of appeal. Since it was organised on the basis of the tribes, its rules and procedures were nearly identical to those of the Comitia Tributa. Each magistrate was vested with a degree of maior potestas (“major power”). Each magistrate could veto any action that was taken by a magistrate of an equal or lower rank. Plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles, on the other hand, were independent of the other magistrates. Magisterial powers, and checks on those powers. Each republican magistrate held certain constitutional powers. Only the People of Rome (both plebeians and patricians) had the right to confer these powers on any individual magistrate. The most powerful constitutional power was imperium. Imperium was held by both consuls and praetors. Imperium gave a magistrate the authority to command a military force. All magistrates also had the power of coercion. This was used by magistrates to maintain public order. While in Rome, all citizens had a judgement against coercion. This protection was called provocatio (see below). Magistrates also had both the power and the duty to look for omens. This power would often be used to obstruct political opponents. One check on a magistrate’s power was his collegiality. Each magisterial office would be held concurrently by at least two people. Another such check was provocatio. Provocatio was a primordial form of due process. It was a precursor to habeas corpus. This created problems for some consuls and praetors, and these magistrates would occasionally have their imperium extended. In effect, they would retain the powers of the office (as a promagistrate), without officially holding that office. Consuls, Praetors, Censors, Aediles, Quaestors, Tribunes, and Dictators. Of Marius, had been put on full display. The populares party took full advantage of this opportunity by allying itself with Marius. Several years later, in 88 BC, a Roman army was sent to put down an emerging Asian power, king Mithridates of Pontus. The army, however, was defeated. One of Marius’ old quaestors, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, had been elected consul for the year, and was ordered by the senate to assume command of the war against Mithridates. Marius, a member of the ” populares ” party, had a tribune revoke Sulla’s command of the war against Mithridates. Sulla, a member of the aristocratic (” optimates “) party, brought his army back to Italy and marched on Rome. Sulla was so angry at Marius’ tribune that he passed a law intended to permanently weaken the tribunate. With Sulla gone, the populares under Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna soon took control of the city. During the period in which the populares party controlled the city, they flouted convention by re-electing Marius consul several times without observing the customary ten-year interval between offices. They also transgressed the established oligarchy by advancing unelected individuals to magisterial office, and by substituting magisterial edicts for popular legislation. Sulla soon made peace with Mithridates. Sulla and his supporters then slaughtered most of Marius’ supporters. Sulla, having observed the violent results of radical popular reforms, was naturally conservative. As such, he sought to strengthen the aristocracy, and by extension the senate. Sulla made himself dictator, passed a series of constitutional reforms, resigned the dictatorship, and served one last term as consul. He died in 78 BC. Pompey, Crassus and the Catilinarian Conspiracy. A Roman marble head of Pompey (now found in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek). In 77 BC, the senate sent one of Sulla’s former lieutenants, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”), to put down an uprising in Spain. Around the same time, another of Sulla’s former lieutenants, Marcus Licinius Crassus, had just put down the Spartacus led gladiator/slave revolt in Italy. Upon their return, Pompey and Crassus found the populares party fiercely attacking Sulla’s constitution. They attempted to forge an agreement with the populares party. If both Pompey and Crassus were elected consul in 70 BC, they would dismantle the more obnoxious components of Sulla’s constitution. The two were soon elected, and quickly dismantled most of Sulla’s constitution. Around 66 BC, a movement to use constitutional, or at least peaceful, means to address the plight of various classes began. After several failures, the movement’s leaders decided to use any means that were necessary to accomplish their goals. The movement coalesced under an aristocrat named Lucius Sergius Catilina. The movement was based in the town of Faesulae, which was a natural hotbed of agrarian agitation. The rural malcontents were to advance on Rome, and be aided by an uprising within the city. After assassinating the consuls and most of the senators, Catiline would be free to enact his reforms. The conspiracy was set in motion in 63 BC. The consul for the year, Marcus Tullius Cicero, intercepted messages that Catiline had sent in an attempt to recruit more members. As a result, the top conspirators in Rome (including at least one former consul) were executed by authorisation (of dubious constitutionality) of the senate, and the planned uprising was disrupted. Cicero then sent an army, which cut Catiline’s forces to pieces. The most important result of the Catilinarian conspiracy was that the populares party became discredited. The prior 70 years had witnessed a gradual erosion in senatorial powers. The violent nature of the conspiracy, in conjunction with the senate’s skill in disrupting it, did a great deal to repair the senate’s image. The Senate, elated by its successes against Catiline, refused to ratify the arrangements that Pompey had made. Pompey, in effect, became powerless. Caesar and Pompey, along with Crassus, established a private agreement, now known as the First Triumvirate. Under the agreement, Pompey’s arrangements would be ratified. Caesar would be elected consul in 59 BC, and would then serve as governor of Gaul for five years. Crassus was promised a future consulship. Caesar became consul in 59 BC. His colleague, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, was an extreme aristocrat. Caesar submitted the laws that he had promised Pompey to the assemblies. Bibulus attempted to obstruct the enactment of these laws, and so Caesar used violent means to ensure their passage. Caesar was then made governor of three provinces. He facilitated the election of the former patrician Publius Clodius Pulcher to the tribunate for 58 BC. Clodius set about depriving Caesar’s senatorial enemies of two of their more obstinate leaders in Cato and Cicero. Clodius was a bitter opponent of Cicero because Cicero had testified against him in a sacrilege case. Clodius attempted to try Cicero for executing citizens without a trial during the Catiline conspiracy, resulting in Cicero going into self-imposed exile and his house in Rome being burnt down. Clodius also passed a bill that forced Cato to lead the invasion of Cyprus which would keep him away from Rome for some years. Clodius also passed a bill that gave the populace a free grain dole, which had previously just been subsidised. The end of the First Triumvirate. Clodius formed armed gangs that terrorised the city and eventually began to attack Pompey’s followers, who in response funded counter-gangs formed by Titus Annius Milo. The political alliance of the triumvirate was crumbling. Domitius Ahenobarbus ran for the consulship in 55 BC promising to take Caesar’s command from him. Eventually, the triumvirate was renewed at Lucca. Pompey and Crassus were promised the consulship in 55 BC, and Caesar’s term as governor was extended for five years. Crassus led an ill-fated expedition with legions led by his son, Caesar’s lieutenant, against the Kingdom of Parthia. This resulted in his defeat and death at the Battle of Carrhae. Finally, Pompey’s wife, Julia, who was Caesar’s daughter, died in childbirth. This event severed the last remaining bond between Pompey and Caesar. Beginning in the summer of 54 BC, a wave of political corruption and violence swept Rome. This chaos reached a climax in January of 52 BC, when Clodius was murdered in a gang war by Milo. On 1 January 49 BC, an agent of Caesar presented an ultimatum to the senate. The ultimatum was rejected, and the senate then passed a resolution which declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July of that year, he would be considered an enemy of the Republic. On 7 January of 49 BC, the senate passed a senatus consultum ultimum , which vested Pompey with dictatorial powers. Pompey’s army, however, was composed largely of untested conscripts. On 10 January, Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his veteran army (in violation of Roman laws) and marched towards Rome. Caesar’s rapid advance forced Pompey, the consuls and the Senate to abandon Rome for Greece. Caesar entered the city unopposed. The period of transition (49-29 BC). By 29 BC, Rome had completed its transition from being a city-state with a network of dependencies, to being the capital of a world empire. With Pompey defeated and order restored, Caesar wanted to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed. The powers which he would give himself would ultimately be used by his imperial successors. He would assume these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome’s other political institutions. Caesar would hold both the dictatorship and the tribunate, but alternated between the consulship and the proconsulship. In 48 BC, Caesar was given permanent tribunician powers. This made his person sacrosanct, gave him the power to veto the senate, and allowed him to dominate the Plebeian Council. In 46 BC, Caesar was given censorial powers, which he used to fill the senate with his own partisans. Caesar then raised the membership of the Senate to 900. This robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made it increasingly subservient to him. While the assemblies continued to meet, he submitted all candidates to the assemblies for election, and all bills to the assemblies for enactment. Thus, the assemblies became powerless and were unable to oppose him. Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire. Since his absence from Rome would limit his ability to install his own consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates in 43 BC, and all consuls and tribunes in 42 BC. This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people to being representatives of the dictator. Caesar’s assassination and the Second Triumvirate. Caesar was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC. The assassination was led by Gaius Cassius and Marcus Brutus. Most of the conspirators were senators, who had a variety of economic, political, or personal motivations for carrying out the assassination. Many were afraid that Caesar would soon resurrect the monarchy and declare himself king. Others feared loss of property or prestige as Caesar carried out his land reforms in favor of the landless classes. Virtually all the conspirators fled the city after Caesar’s death in fear of retaliation. The civil war that followed destroyed what was left of the Republic. After the assassination, Mark Antony formed an alliance with Caesar’s adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian. Along with Marcus Lepidus, they formed an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate. They held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution. As such, the Senate and assemblies remained powerless, even after Caesar had been assassinated. The conspirators were then defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC. Eventually, however, Antony and Octavian fought against each other in one last battle. Antony was defeated in the naval Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and he committed suicide with his love, Cleopatra. Julius Caesar, from the bust in the British Museum, in Cassell’s History of England (1902). Life in the Roman Republic revolved around the city of Rome, and its famed seven hills. The city also had several theatres, gymnasiums, and many taverns, baths and brothels. Throughout the territory under Rome’s control, residential architecture ranged from very modest houses to country villas, and in the capital city of Rome, to the residences on the elegant Palatine Hill, from which the word ” palace ” is derived. The vast majority of the population lived in the city center, packed into apartment blocks. Most Roman towns and cities had a forum and temples, as did the city of Rome itself. Aqueducts brought water to urban centers and wine and cooking oil were imported from abroad. Landlords generally resided in cities and left their estates in the care of farm managers. To stimulate a higher labour productivity, many landlords freed large numbers of slaves. Beginning in the middle of the 2nd century BC, Greek culture was increasingly ascendant, in spite of tirades against the “softening” effects of Hellenised culture. By the time of Augustus, cultured Greek household slaves taught the Roman young (sometimes even the girls). Greek sculptures adorned Hellenistic landscape gardening on the Palatine or in the villas, and much of Roman cuisine was essentially Greek. Roman writers disdained Latin for a cultured Greek style. Social history and structure. Many aspects of Roman culture were borrowed from the Greeks. In architecture and sculpture, the difference between Greek models and Roman paintings are apparent. The chief Roman contributions to architecture were the arch and the dome. Rome has also had a tremendous impact on European cultures following it. Its significance is perhaps best reflected in its endurance and influence, as is seen in the longevity and lasting importance of works of Virgil and Ovid. Latin, the Republic’s primary language, remains used for liturgical purposes by the Roman Catholic Church, and up to the 19th century was used extensively in scholarly writings in, for example, science and mathematics. Roman law laid the foundations for the laws of many European countries and their colonies. The center of the early social structure was the family, which was not only marked by blood relations but also by the legally constructed relation of patria potestas. The Pater familias was the absolute head of the family; he was the master over his wife, his children, the wives of his sons, the nephews, the slaves and the freedmen, disposing of them and of their goods at will, even putting them to death. Roman law recognised only patrician families as legal entities. Generally, mutilation and murder of slaves was prohibited by legislation. It is estimated that over 25% of the Roman population was enslaved. Roman clad in a toga. Men typically wore a toga, and women a stola. The woman’s stola differed in looks from a toga, and was usually brightly coloured. The cloth and the dress distinguished one class of people from the other class. The tunic worn by plebeians, or common people, like shepherds and slaves, was made from coarse and dark material, whereas the tunic worn by patricians was of linen or white wool. A knight or magistrate would wear an augusticlavus , a tunic bearing small purple studs. Senators wore tunics with broad red stripes, called tunica laticlavia. Military tunics were shorter than the ones worn by civilians. Boys, up until the festival of Liberalia, wore the toga praetexta , which was a toga with a crimson or purple border. The toga virilis , (or toga pura) was worn by men over the age of 16 to signify their citizenship in Rome. The toga picta was worn by triumphant generals and had embroidery of their skill on the battlefield. The toga pulla was worn when in mourning. Even footwear indicated a person’s social status. Patricians wore red and orange sandals, senators had brown footwear, consuls had white shoes, and soldiers wore heavy boots. The Romans also invented socks for those soldiers required to fight on the northern frontiers, sometimes worn in sandals. Romans had simple food habits. Staple food was generally consumed at around 11 o’clock, and consisted of bread, salad, cheese, fruits, nuts, and cold meat left over from the dinner the night before. The Roman poet, Horace mentions another Roman favorite, the olive, in reference to his own diet, which he describes as very simple: As for me, olives, endives, and smooth mallows provide sustenance. The family ate together, sitting on stools around a table. Fingers were used to eat solid foods and spoons were used for soups. Wine was considered a staple drink, consumed at all meals and occasions by all classes and was quite cheap. Cato the Elder once advised cutting his rations in half to conserve wine for the workforce. Many types of drinks involving grapes and honey were consumed as well. Drinking on an empty stomach was regarded as boorish and a sure sign for alcoholism, the debilitating physical and psychological effects of which were known to the Romans. An accurate accusation of being an alcoholic was an effective way to discredit political rivals. Prominent Roman alcoholics included Mark Antony, and Cicero’s own son Marcus (Cicero Minor). Even Cato the Younger was known to be a heavy drinker. Following various military conquests in the Greek East, Romans adapted a number of Greek educational precepts to their own fledgling system. Physical training to prepare the boys to grow as Roman citizens and for eventual recruitment into the army. Conforming to discipline was a point of great emphasis. Girls generally received instruction from their mothers in the art of spinning, weaving, and sewing. Schooling in a more formal sense was begun around 200 BC. Education began at the age of around six, and in the next six to seven years, boys and girls were expected to learn the basics of reading, writing and counting. By the age of twelve, they would be learning Latin, Greek, grammar and literature, followed by training for public speaking. Oratory was an art to be practiced and learnt, and good orators commanded respect. The native language of the Romans was Latin. Although surviving Latin literature consists almost entirely of Classical Latin, an artificial and highly stylised and polished literary language from the 1st century BC, the actual spoken language was Vulgar Latin, which significantly differed from Classical Latin in grammar, vocabulary, and eventually pronunciation. Rome’s expansion spread Latin throughout Europe, and over time Vulgar Latin evolved and dialectised in different locations, gradually shifting into a number of distinct Romance languages. Many of these languages, including French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian and Spanish, flourished, the differences between them growing greater over time. Although English is Germanic rather than Roman in origin, English borrows heavily from Latin and Latin-derived words. Roman literature was from its very inception influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are of historical epics telling the early military history of Rome. As the republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy. Virgil represents the pinnacle of Roman epic poetry. His Aeneid tells the story of flight of Aeneas from Troy and his settlement of the city that would become Rome. Lucretius, in his On the Nature of Things , attempted to explicate science in an epic poem. The genre of satire was common in Rome, and satires were written by, among others, Juvenal and Persius. The rhetorical works of Cicero are considered to be some of the best bodies of correspondence recorded in antiquity. In the 3rd century BC, Greek art taken as booty from wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists. Portrait sculpture during the period utilised youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, often depicting Roman victories. Music was a major part of everyday life. The word itself derives from Greek (mousike), “(art) of the Muses”. Many private and public events were accompanied by music, ranging from nightly dining to military parades and manoeuvres. In a discussion of any ancient music, however, non-specialists and even many musicians have to be reminded that much of what makes our modern music familiar to us is the result of developments only within the last 1,000 years; thus, our ideas of melody, scales, harmony, and even the instruments we use would not be familiar to Romans who made and listened to music many centuries earlier. Over time, Roman architecture was modified as their urban requirements changed, and the civil engineering and building construction technology became developed and refined. The Roman concrete has remained a riddle, and even after more than 2,000 years some Roman structures still stand magnificently. The architectural style of the capital city was emulated by other urban centers under Roman control and influence. Roman cities were well planned, efficiently managed and neatly maintained. The city of Rome had a place called the Campus Martius (“Field of Mars”), which was a sort of drill ground for Roman soldiers. Later, the Campus became Rome’s track and field playground. In the campus, the youth assembled to play and exercise, which included jumping, wrestling, boxing and racing. Equestrian sports, throwing, and swimming were also preferred physical activities. In the countryside, pastime included fishing and hunting. Board games played in Rome included dice (Tesserae or Tali), Roman Chess (Latrunculi), Roman Checkers (Calculi), Tic-tac-toe (Terni Lapilli), and Ludus duodecim scriptorum and Tabula, predecessors of backgammon. There were several other activities to keep people engaged like chariot races, musical and theatrical performances. Roman religious beliefs date back to the founding of Rome, around 800 BC. However, the Roman religion commonly associated with the republic and early empire did not begin until around 500 BC, when Romans came in contact with Greek culture, and adopted many of the Greek religious beliefs. Private and personal worship was an important aspect of religious practices. In a sense, each household was a temple to the gods. Each household had an altar (lararium), at which the family members would offer prayers, perform rites, and interact with the household gods. Many of the gods that Romans worshiped came from the Proto-Indo-European pantheon, others were based on Greek gods. The two most famous deities were Jupiter (the king God) and Mars (the god of war). With its cultural influence spreading over most of the Mediterranean, Romans began accepting foreign gods into their own culture, as well as other philosophical traditions such as Cynicism and Stoicism. The structural history of the Roman military describes the major chronological transformations in the organisation and constitution of the Roman armed forces. The Roman military was split into the Roman army and the Roman navy, although these two branches were less distinct than they tend to be in modern defence forces. Within the top-level branches of army and navy, structural changes occurred both as a result of positive military reform and through organic structural evolution. During this period, Roman soldiers seem to have been modelled after those of the Etruscans to the north, who themselves seem to have copied their style of warfare from the Greeks. Traditionally, the introduction of the phalanx formation into the Roman army is ascribed to the city’s penultimate king, Servius Tullius (ruled 578 to 534 BC). Each subsequent rank consisted of those with less wealth and poorer equipment than the one before it. One disadvantage of the phalanx was that it was only effective when fighting in large, open spaces, which left the Romans at a disadvantage when fighting in the hilly terrain of central Italian peninsula. In the 4th century BC, the Romans abandoned the phalanx in favour of the more flexible manipular formation. This change is sometimes attributed to Marcus Furius Camillus and placed shortly after the Gallic invasion of 390 BC; it is more likely, however, that they were copied from Rome’s Samnite enemies to the south, possibly as a result of Samnite victories during the Second Samnite War (326 to 304 BC). During this period, an army formation of around 5,000 men (of both heavy and light infantry) was known as a legion. The manipular army was based upon social class, age and military experience. Maniples were units of 120 men each drawn from a single infantry class. The maniples were typically deployed into three discrete lines based on the three heavy infantry types. Each first line maniple were leather-armoured infantry soldiers who wore a bronze breastplate and a bronze helmet adorned with 3 feathers approximately 30 cm (12 in) in height and carried an iron-clad wooden shield. They were armed with a sword and two throwing spears. The second infantry line was armed and armoured in the same manner as was the first infantry line. The third infantry line was the last remnant of the hoplite-style (the Greek-style formation used occasionally during the early Republic) troops in the Roman army. They were armed and armoured in the same manner as were the soldiers in the second line, with the exception that they carried a lighter spear. The three infantry classes may have retained some slight parallel to social divisions within Roman society, but at least officially the three lines were based upon age and experience rather than social class. Young, unproven men would serve in the first line, older men with some military experience would serve in the second line, and veteran troops of advanced age and experience would serve in the third line. The heavy infantry of the maniples were supported by a number of light infantry and cavalry troops, typically 300 horsemen per manipular legion. The cavalry was drawn primarily from the richest class of equestrians. There was an additional class of troops who followed the army without specific martial roles and were deployed to the rear of the third line. Their role in accompanying the army was primarily to supply any vacancies that might occur in the maniples. The light infantry consisted of 1,200 unarmoured skirmishing troops drawn from the youngest and lower social classes. They were armed with a sword and a small shield, as well as several light javelins. Rome’s military confederation with the other peoples of the Italian peninsula meant that half of Rome’s army was provided by the Socii, such as the Etruscans, Umbrians, Apulians, Campanians, Samnites, Lucani, Bruttii, and the various southern Greek cities. Polybius states that Rome could draw on 770,000 men at the beginning of the Second Punic War, of which 700,000 were infantry and 70,000 met the requirements for cavalry. Rome’s Italian allies would be organized in alae , or wings , roughly equal in manpower to the Roman legions, though with 900 cavalry instead of 300. A small navy had operated at a fairly low level after about 300 BC, but it was massively upgraded about forty years later, during the First Punic War. After a period of frenetic construction, the navy mushroomed to a size of more than 400 ships on the Carthaginian (“Punic”) pattern. Once completed, it could accommodate up to 100,000 sailors and embarked troops for battle. The navy thereafter declined in size. The extraordinary demands of the Punic Wars, in addition to a shortage of manpower, exposed the tactical weaknesses of the manipular legion, at least in the short term. In 217 BC, near the beginning of the Second Punic War, Rome was forced to effectively ignore its long-standing principle that its soldiers must be both citizens and property owners. During the 2nd century BC, Roman territory saw an overall decline in population, partially due to the huge losses incurred during various wars. This was accompanied by severe social stresses and the greater collapse of the middle classes. As a result, the Roman state was forced to arm its soldiers at the expense of the state, which it had not had to do in the past. The distinction between the heavy infantry types began to blur, perhaps because the state was now assuming the responsibility of providing standard-issue equipment. In addition, the shortage of available manpower led to a greater burden being placed upon Rome’s allies for the provision of allied troops. Eventually, the Romans were forced to begin hiring mercenaries to fight alongside the legions. The legion after the reforms of Gaius Marius (107-27 BC). Bust of Gaius Marius, instigator of the Marian reforms. In a process known as the Marian reforms, Roman consul Gaius Marius carried out a programme of reform of the Roman military. In 107 BC, all citizens, regardless of their wealth or social class, were made eligible for entry into the Roman army. This move formalised and concluded a gradual process that had been growing for centuries, of removing property requirements for military service. The distinction between the three heavy infantry classes, which had already become blurred, had collapsed into a single class of heavy legionary infantry. The heavy infantry legionaries were drawn from citizen stock, while non-citizens came to dominate the ranks of the light infantry. The army’s higher-level officers and commanders were still drawn exclusively from the Roman aristocracy. Unlike earlier in the Republic, legionaries were no longer fighting on a seasonal basis to protect their land. Instead, they received standard pay, and were employed by the state on a fixed-term basis. As a consequence, military duty began to appeal most to the poorest sections of society, to whom a salaried pay was attractive. A destabilising consequence of this development was that the proletariat acquired a stronger and more elevated position within the state. The legions of the late Republic were, structurally, almost entirely heavy infantry. The legion’s main sub-unit was called a cohort and consisted of approximately 480 infantrymen. The cohort was therefore a much larger unit than the earlier maniple sub-unit, and was divided into six centuries of 80 men each. Each century was separated further into 10 “tent groups” of 8 men each. Legions additionally consisted of a small body, typically 120 men, of Roman legionary cavalry. The cavalry troops were used as scouts and dispatch riders rather than battlefield cavalry. Legions also contained a dedicated group of artillery crew of perhaps 60 men. Each legion was normally partnered with an approximately equal number of allied (non-Roman) troops. However, the most obvious deficiency of the Roman army remained its shortage of cavalry, especially heavy cavalry. As Rome’s borders expanded and its adversaries changed from largely infantry-based to largely cavalry-based troops, the infantry-based Roman army began to find itself at a tactical disadvantage, particularly in the East. After having declined in size following the subjugation of the Mediterranean, the Roman navy underwent short-term upgrading and revitalisation in the late Republic to meet several new demands. Under Caesar, an invasion fleet was assembled in the English Channel to allow the invasion of Britannia ; under Pompey, a large fleet was raised in the Mediterranean Sea to clear the sea of Cilician pirates. During the civil war that followed, as many as a thousand ships were either constructed or pressed into service from Greek cities. The core of the campaign history of the Roman Republican military is the account of the Roman military’s land battles. Despite the encompassing of lands around the periphery of the Mediterranean sea, naval battles were typically less significant than land battles to the military history of Rome. As with most ancient civilisations, Rome’s military served the triple purposes of securing its borders, exploiting peripheral areas through measures such as imposing tribute on conquered peoples, and maintaining internal order. From the outset, Rome’s military typified this pattern and the majority of Rome’s campaigns were characterised by one of two types. The first is the territorial expansionist campaign, normally begun as a counter-offensive, in which each victory brought subjugation of large areas of territory. The second is the civil war, of which examples plagued the Roman Republic in its final century. Roman armies were not invincible, despite their formidable reputation and host of victories. Over the centuries the Romans ” produced their share of incompetents ” who led Roman armies into catastrophic defeats. Nevertheless, it was generally the fate of even the greatest of Rome’s enemies, such as Pyrrhus and Hannibal, to win the battle but lose the war. The history of Rome’s campaigning is, if nothing else, a history of obstinate persistence overcoming appalling losses. Early Republic (458-274 BC) Early Italian campaigns (458-396 BC). The first Roman republican wars were wars of both expansion and defence, aimed at protecting Rome itself from neighbouring cities and nations and establishing its territory in the region. Initially, Rome’s immediate neighbours were either Latin towns and villages, or else tribal Sabines from the Apennine hills beyond. One by one Rome defeated both the persistent Sabines and the local cities that were either under Etruscan control or else Latin towns that had cast off their Etruscan rulers. Rome defeated Latin cities in the Battle of Lake Regillus in 496 BC, the Battle of Mons Algidus in 458 BC, the Battle of Corbione in 446 BC, the Battle of Aricia, and an Etruscan city in the Battle of the Cremera in 477 BC. By the end of this period, Rome had effectively completed the conquest of their immediate Etruscan and Latin neighbours, as well as secured their position against the immediate threat posed by the tribespeople of the nearby Apennine hills. Celtic invasion of Italia (390-387 BC). By 390 BC, several Gallic tribes had begun invading Italy from the north as their culture expanded throughout Europe. The Romans were alerted of this when a particularly warlike tribe invaded two Etruscan towns from the north. These two towns were not far from Rome’s sphere of influence. These towns, overwhelmed by the size of the enemy in numbers and ferocity, called on Rome for help. The Romans met them in pitched battle at the Battle of Allia River around 390-387 BC. The Gauls, under their chieftain Brennus, defeated the Roman army of around 15,000 troops and proceeded to pursue the fleeing Romans back to Rome itself and sacked the city before being either driven off or bought off. Now that the Romans and Gauls had bloodied one another, intermittent warfare was to continue between the two in Italy for more than two centuries. The Celtic problem would not be resolved for Rome until the final subjugation of all Gaul by Julius Caesar at the Battle of Alesia in 52 BC. Roman expansion into Italia (343-282 BC). After recovering surprisingly swiftly from the sack of Rome, the Romans immediately resumed their expansion within Italy. The First Samnite War of between 343 BC and 341 BC was a relatively short affair: the Romans beat the Samnites in two battles, but were forced to withdraw from the war before they could pursue the conflict further due to the revolt of several of their Latin allies in the Latin War. Rome bested the Latins in the Battle of Vesuvius and again in the Battle of Trifanum, after which the Latin cities were obliged to submit to Roman rule. The Second Samnite War, from 327 BC to 304 BC, was a much longer and more serious affair for both the Romans and Samnites. The fortunes of the two sides fluctuated throughout its course. The Romans then proved victorious at the Battle of Bovianum and the tide turned strongly against the Samnites from 314 BC onwards, leading them to sue for peace with progressively less generous terms. By 304 BC the Romans had effectively annexed the greater degree of the Samnite territory, founding several colonies. Seven years after their defeat, with Roman dominance of the area looking assured, the Samnites rose again and defeated a Roman army in 298 BC, to open the Third Samnite War. With this success in hand they managed to bring together a coalition of several previous enemies of Rome. In the Battle of Populonia in 282 BC Rome finished off the last vestiges of Etruscan power in the region. Pyrrhic War (280-275 BC). Route of Pyrrhus of Epirus. By the beginning of the 3rd century, Rome had established itself as a major power on the Italian Peninsula, but had not yet come into conflict with the dominant military powers in the Mediterranean Basin at the time: Carthage and the Greek kingdoms. When a diplomatic dispute between Rome and a Greek colony erupted into open warfare in a naval confrontation, the Greek colony appealed for military aid to Pyrrhus, ruler of the northwestern Greek kingdom of Epirus. Motivated by a personal desire for military accomplishment, Pyrrhus landed a Greek army of some 25,000 men on Italian soil in 280 BC. Despite early victories, Pyrrhus found his position in Italy untenable. Rome steadfastly refused to negotiate with Pyrrhus as long as his army remained in Italy. Facing unacceptably heavy losses with each encounter with the Roman army, Pyrrhus withdrew from the peninsula (thus deriving the term “pyrrhic victory”). In 275 BC, Pyrrhus again met the Roman army at the Battle of Beneventum. While Beneventum was indecisive, Pyrrhus realised his army had been exhausted and reduced, by years of foreign campaigns, and seeing little hope for further gains, he withdrew completely from Italy. The conflicts with Pyrrhus would have a great effect on Rome. Rome had shown it was capable of pitting its armies successfully against the dominant military powers of the Mediterranean, and that the Greek kingdoms were incapable of defending their colonies in Italy and abroad. Rome quickly moved into southern Italia, subjugating and dividing the Greek colonies. Now, Rome effectively dominated the Italian peninsula, and won an international military reputation. Mid-Republic (274-148 BC) Punic Wars (264-146 BC). Theatre of the Punic Wars. The First Punic War began in 264 BC when settlements on Sicily began to appeal to the two powers between which they lay – Rome and Carthage – to solve internal conflicts. The war saw land battles in Sicily early on, but the theatre shifted to naval battles around Sicily and Africa. Before the First Punic War there was no Roman navy to speak of. The new war in Sicily against Carthage, a great naval power, forced Rome to quickly build a fleet and train sailors. The first few naval battles were catastrophic disasters for Rome. However, after training more sailors and inventing a grappling engine, a Roman naval force was able to defeat a Carthaginian fleet, and further naval victories followed. The Carthaginians then hired Xanthippus of Carthage, a Spartan mercenary general, to reorganize and lead their army. He managed to cut off the Roman army from its base by re-establishing Carthaginian naval supremacy. With their newfound naval abilities, the Romans then beat the Carthaginians in naval battle again at the Battle of the Aegates Islands and leaving Carthage without a fleet or sufficient coin to raise one. For a maritime power the loss of their access to the Mediterranean stung financially and psychologically, and the Carthaginians sued for peace. Continuing distrust led to the renewal of hostilities in the Second Punic War when Hannibal Barca attacked a Spanish town, which had diplomatic ties to Rome. Hannibal then crossed the Italian Alps to invade Italy. Hannibal’s successes in Italy began immediately, and reached an early climax at the Battle of Cannae, where 70,000 Romans were killed. In three battles, the Romans managed to hold off Hannibal but then Hannibal smashed a succession of Roman consular armies. By this time Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal Barca sought to cross the Alps into Italy and join his brother with a second army. Hasdrubal managed to break through into Italy only to be defeated decisively on the Metaurus River. Unable to defeat Hannibal himself on Italian soil, the Romans boldly sent an army to Africa under Scipio Africanus with the intention of threatening the Carthaginian capital. Hannibal was recalled to Africa, and defeated at the Battle of Zama. Carthage never managed to recover after the Second Punic War. And the Third Punic War that followed was in reality a simple punitive mission to raze the city of Carthage to the ground. Carthage was almost defenseless and when besieged offered immediate surrender, conceding to a string of outrageous Roman demands. The Romans refused the surrender, and the city was stormed after a short siege and completely destroyed. Ultimately, all of Carthage’s North African and Spanish territories were acquired by Rome. Kingdom of Macedonia, the Greek poleis, and Illyria (215-148 BC). Rome’s preoccupation with its war with Carthage provided an opportunity for Philip V of the kingdom of Macedonia, located in the north of the Greek peninsula, to attempt to extend his power westward. Philip sent ambassadors to Hannibal’s camp in Italy, to negotiate an alliance as common enemies of Rome. However, Rome discovered the agreement when Philip’s emissaries were captured by a Roman fleet. The First Macedonian War saw the Romans involved directly in only limited land operations, but they ultimately achieved their objective of pre-occupying Philip and preventing him from aiding Hannibal. Macedonia began to encroach on territory claimed by Greek city states in 200 BC and these states pleaded for help from their newfound ally Rome. Rome gave Philip an ultimatum that he must submit several parts of Greater Macedonia to Rome and give up his designs on Greece. Philip refused, and Rome declared war starting the Second Macedonian War. Ultimately, in 197 BC, the Romans decisevely defeated Philip at the Battle of Cynoscephalae, subsequently Macedonia was reduced to a central rump state. Rome now turned its attentions to one of the Greek kingdoms, the Seleucid Empire, in the east. A Roman force defeated the Seleucids at the Battle of Thermopylae and forced them to evacuate Greece. The Romans then pursued the Seleucids beyond Greece, beating them in the decisive engagement of the Battle of Magnesia. In 179 BC, Philip died and his talented and ambitious son, Perseus, took his throne and showed a renewed interest in Greece. Rome declared war on Macedonia again, starting the Third Macedonian War. Perseus initially had some success against the Romans. However, Rome responded by simply sending another stronger army. The second consular army decisively defeated the Macedonians at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC and the Macedonians duly capitulated, ending the Third Macedonian War. The Kingdom of Macedonia was then divided by the Romans into four client republics. The Fourth Macedonian War, fought from 150 BC to 148 BC, was fought against a Macedonian pretender to the throne who was attempting to re-establish the old Kingdom. The Romans swiftly defeated the Macedonians at the Second battle of Pydna. The Achaean League chose this moment to rebel against Roman domination but was swiftly defeated. Corinth was besieged and destroyed in 146 BC, the same year as the destruction of Carthage, which led to the league’s surrender. Late Republic (147-30 BC) Jugurthine War (111-104 BC). The Jugurthine War of 111-104 BC was fought between Rome and Jugurtha of the North African kingdom of Numidia. It constituted the final Roman pacification of Northern Africa, after which Rome largely ceased expansion on the continent after reaching natural barriers of desert and mountain. Following Jugurtha’s usurpation of the throne of Numidia, a loyal ally of Rome since the Punic Wars, Rome felt compelled to intervene. Jugurtha impudently bribed the Romans into accepting his usurpation. Jugurtha was finally captured not in battle but by treachery. The Celtic threat (121 BC) and the new Germanic threat (113-101 BC). In 121 BC, Rome came into contact with two Celtic tribes (from a region in modern France), both of which they defeated with apparent ease. The Cimbrian War (113-101 BC) was a far more serious affair than the earlier clashes of 121 BC. The Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and the Teutons migrated from northern Europe into Rome’s northern territories, and clashed with Rome and her allies. At the Battle of Aquae Sextiae and the Battle of Vercellae both tribes were virtually annihilated, which ended the threat. Internal unrest (135-71 BC). The extensive campaigning abroad by Roman generals, and the rewarding of soldiers with plunder on these campaigns, led to a general trend of soldiers becoming increasingly loyal to their generals rather than to the state. Rome was also plagued by several slave uprisings during this period, in part because vast tracts of land had been given over to slave farming in which the slaves greatly outnumbered their Roman masters. In the last century BC at least twelve civil wars and rebellions occurred. This pattern did not break until Octavian (later Caesar Augustus) ended it by becoming a successful challenger to the Senate’s authority, and was made princeps (emperor). Between 135 BC and 71 BC there were three “Servile Wars” involving slave uprisings against the Roman state. The third and final uprising was the most serious, involving ultimately between 120,000 and 150,000. Slaves under the command of the gladiator Spartacus. Additionally, in 91 BC the Social War broke out between Rome and its former allies in Italy over dissent among the allies that they shared the risk of Rome’s military campaigns, but not its rewards. Although they lost militarily, the allies achieved their objectives with legal proclamations which granted citizenship to more than 500,000 Italians. The internal unrest reached its most serious state, however, in the two civil wars that were caused by the consul Lucius Cornelius Sulla at the beginning of 82 BC. In the Battle of the Colline Gate at the very door of the city of Rome, a Roman army under Sulla bested an army of the Roman Senate and entered the city. Sulla’s actions marked a watershed in the willingness of Roman troops to wage war against one another that was to pave the way for the wars which ultimately overthrew the Republic, and caused the founding of the Roman Empire. Conflicts with Mithridates (89-63 BC) and the Cilician pirates (67 BC). Mithridates the Great was the ruler of Pontus, a large kingdom in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), from 120 to 63 BC. The massacre was the official reason given for the commencement of hostilities in the First Mithradatic War. The Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla forced Mithridates out of Greece proper, but then had to return to Italy to answer the internal threat posed by his rival, Gaius Marius. A peace was made between Rome and Pontus, but this proved only a temporary lull. The Second Mithridatic War began when Rome tried to annex a province that Mithridates claimed as his own. In the Third Mithridatic War, first Lucius Licinius Lucullus and then Pompey the Great were sent against Mithridates. Mithridates was finally defeated by Pompey in the night-time Battle of the Lycus. The Mediterranean had at this time fallen into the hands of pirates, largely from Cilicia. Pompey was nominated as commander of a special naval task force to campaign against the pirates. It took Pompey just forty days to clear the western portion of the sea of pirates and restore communication between Iberia (Spain), Africa, and Italy. Caesar’s early campaigns (59-50 BC). Map of the Gallic Wars. During a term as praetor in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), Pompey’s contemporary Julius Caesar defeated two local tribes in battle. Following his term as consul in 59 BC, he was then appointed to a five-year term as the proconsular Governor of Cisalpine Gaul (current northern Italy), Transalpine Gaul (current southern France) and Illyria (the modern Balkans). Not content with an idle governorship, Caesar strove to find reason to invade Gaul, which would give him the dramatic military success he sought. When two local tribes began to migrate on a route that would take them near (not into) the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul, Caesar had the barely sufficient excuse he needed for his Gallic Wars, fought between 58 BC and 49 BC. Caesar defeated large armies at major battles 58 BC and 57 BC. In 55 and 54 BC he made two expeditions into Britain, becoming the first Roman to do so. Caesar then defeated a union of Gauls at the Battle of Alesia, completing the Roman conquest of Transalpine Gaul. By 50 BC, the entirety of Gaul lay in Roman hands. Gaul never regained its Celtic identity, never attempted another nationalist rebellion, and, other than the crisis of the 3rd century, remained loyal to Rome until the fall of the western empire in 476. Triumvirates and Caesarian ascension (53-30 BC). By 59 BC an unofficial political alliance known as the First Triumvirate was formed between Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”) to share power and influence. In 53 BC, Crassus launched a Roman invasion of the Parthian Empire (modern Iraq and Iran). After initial successes, he marched his army deep into the desert; but here his army was cut off deep in enemy territory, surrounded and slaughtered at the Battle of Carrhae in which Crassus himself perished. The death of Crassus removed some of the balance in the Triumvirate and, consequently, Caesar and Pompey began to move apart. While Caesar was fighting in Gaul, Pompey proceeded with a legislative agenda for Rome that revealed that he was at best ambivalent towards Caesar and perhaps now covertly allied with Caesar’s political enemies. In 51 BC, some Roman senators demanded that Caesar not be permitted to stand for consul unless he turned over control of his armies to the state, which would have left Caesar defenceless before his enemies. Caesar chose civil war over laying down his command and facing trial. By the spring of 49 BC, the hardened legions of Caesar crossed the river Rubicon and swept down the Italian peninsula towards Rome, while Pompey ordered the abandonment of Rome. Afterwards Caesar turned his attention to the Pompeian stronghold of Iberia (modern Spain) but decided to tackle Pompey himself in Greece. Pompey initially defeated Caesar, but failed to follow up on the victory, and was decisively defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, despite outnumbering Caesar’s forces two to one, albeit with inferior quality troops. Pompey fled again, this time to Egypt, where he was murdered. Pompey’s death did not result in an end to the civil war as Caesar’s enemies were manifold and continued to fight on. In 46 BC Caesar lost perhaps as much as a third of his army, but ultimately came back to defeat the Pompeian army of Metellus Scipio in the Battle of Thapsus, after which the Pompeians retreated yet again to Iberia. Caesar then defeated the combined Pompeian forces at the Battle of Munda. Caesar was now the primary figure of the Roman state, enforcing and entrenching his powers and his enemies feared that he had ambitions to become an autocratic ruler. Arguing that the Roman Republic was in danger a group of senators hatched a conspiracy and murdered Caesar in the Senate in March 44 BC. Mark Antony, Caesar’s lieutenant, condemned Caesar’s assassination, and war broke out between the two factions. Antony was denounced as a public enemy, and Caesar’s adopted son and chosen heir, Gaius Octavian, was entrusted with the command of the war against him. At the Battle of Mutina Antony was defeated by the consuls Hirtius and Pansa, who were both killed. Octavian came to terms with Caesarians Antony and Lepidus in 43 BC when the Second Triumvirate was formed. In 42 BC Triumvirs Mark Antony and Octavian fought the Battle of Philippi with Caesar’s assassins Brutus and Cassius. Although Brutus defeated Octavian, Antony defeated Cassius, who committed suicide. Brutus joined him shortly afterwards. However, civil war flared again when the Second Triumvirate of Octavian, Lepidus and Mark Antony failed. The ambitious Octavian built a power base of patronage and then launched a campaign against Mark Antony. At the naval Battle of Actium off the coast of Greece, Octavian decisively defeated Antony and Cleopatra. Octavian was granted a series of special powers including sole “imperium” within the city of Rome, permanent consular powers and credit for every Roman military victory, since all future generals were assumed to be acting under his command. In 27 BC Octavian was granted the use of the names “Augustus” and “Princeps” indicating his primary status above all other Romans, and he adopted the title “Imperator Caesar” making him the first Roman Emperor. World-renowned expert numismatist, enthusiast, author and dealer in authentic ancient Greek, ancient Roman, ancient Byzantine, world coins & more. Ilya Zlobin is an independent individual who has a passion for coin collecting, research and understanding the importance of the historical context and significance all coins and objects represent. Send me a message about this and I can update your invoice should you want this method. Getting your order to you, quickly and securely is a top priority and is taken seriously here. Great care is taken in packaging and mailing every item securely and quickly. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Additionally, the coin is inside it’s own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2×2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. Whether your goal is to collect or give the item as a gift, coins presented like this could be more prized and valued higher than items that were not given such care and attention to. When should I leave feedback? Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens sometimes that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for their order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. How and where do I learn more about collecting ancient coins? Visit the “Guide on How to Use My Store”. For on an overview about using my store, with additional information and links to all other parts of my store which may include educational information on topics you are looking for. The item “SULLA’s General as IMPERATOR 81BC Silver Roman Republic Coin ELEPHANT NGC i67613″ is in sale since Monday, February 19, 2018. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ Ancient\Roman\ Republic (300 BC-27 BC)”. The seller is “highrating_lowprice” and is located in Rego Park, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Composition: Silver

- Certification: NGC

- Era: Roman: Republic

- Material: Silver

- Denomination: Denarius

- Certification Number: 4281369-007

- Grade: VF

Comments Off

Filed under sulla's

SELEUKOS I Nikator Seleukid Tetradrachm ELEPHANTS Silver Greek Coin NGC i68725