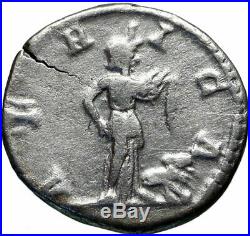

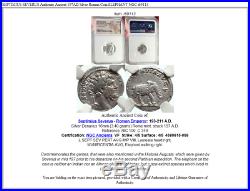

Item: i52147 Authentic Ancient Coin of. Septimius Severus – Roman Emperor : 193-211 A. Silver Denarius 19mm (3.02 grams) Rome mint: 207 A. Reference: RIC 207; Sear 6341; RSC 493. SEVERVS PIVS AVG, laureate head right P M TR P XV COS III P P, Africa wearing elephant-skin head-dress standing right, holding out folds of drapery containing fruits, lion at feet walking right. The Roman province of Africa Proconsularis was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day northern Tunisia , the northeast of modern-day Algeria , and the small Mediterranean Sea coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor. It was the richest province in the western part of the empire. The Arabs later named roughly the same region as the original province Ifriqiya , a rendering of Africa , from the Latin language. The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian (ruled 117138 AD), showing, in northern Africa, the senatorial province of Africa Proconsularis E. 1 legion deployed in 125. Northern Africa under Roman rule. Further information: History of Tunisia , History of Algeria , History of Africa , Numidia and Mauretania. The land acquired for the province of Africa was the site of the ancient city of Carthage. Other large cities in the region included Hadrumetum (modern Sousse , Tunisia), capital of Byzacena , Hippo Regius (modern Annaba , Algeria). The province was established by the Roman Republic in 146 BC, following the Third Punic War. Rome established its first African colony, Africa Proconsularis or Africa Vetus (Old Africa), governed by a proconsul , in the most fertile part of what was formerly Carthaginian territory. Utica was formed as the administrative capital. The remaining territory was left in the domain of the Numidian client king Massinissa. At this time, the Roman policy in Africa was simply to prevent another great power from rising on the far side of Sicily. In 118 BC, the Numidian prince Jugurtha attempted to reunify the smaller kingdoms. However, upon his death, much of Jugurtha’s territory was placed in the control of the Mauretanian client king Bocchus ; and, by that time, the romanization of Africa was firmly rooted. In 27 BC, when the Republic had transformed into an Empire , the province of Africa began its Imperial occupation under Roman rule. Électrum tridrachme struck at Zeugitane in Carthage. Several political and provincial reforms were implemented by Augustus and later by Caligula , but Claudius finalized the territorial divisions into official Roman provinces. Africa was a senatorial province. After Diocletian’s administrative reforms, it was split into Africa Zeugitana (which retained the name Africa Proconsularis , as it was governed by a proconsul) in the north and Africa Byzacena in the south, both of which were part of the Dioecesis Africae. The region remained a part of the Roman Empire until the Germanic migrations of the 5th century. The Vandals crossed into North Africa from Spain in 429 and overran the area by 439 and founded their own kingdom, including Sicily , Corsica , Sardinia and the Balearics. The Vandals controlled the country as a warrior-elite, enforcing a policy of strict separation and suppressing the local Romano-African population. They also persecuted the Catholicism , as the Vandals were adherents of the Arianism (the semi-trinitarian doctrines of Arius, a priest of Egypt). In 476, when the Western Roman Empire , had finally fallen , it became a remnant of the Empire. Towards the end of the 5th century, the Vandal state fell into decline, abandoning most of the interior territories to the Mauri and other Berber tribes of the desert. In AD 533, Emperor Justinian , using a Vandal dynastic dispute as pretext, sent an army under the general Belisarius to recover Africa. In a short campaign , Belisarius defeated the Vandals, entered Carthage in triumph and reestablished Roman rule over the province. The restored Roman administration was successful in fending off the attacks of the Amazigh desert tribes, and by means of an extensive fortification network managed to extend its rule once again to the interior. The North African provinces, together with the Roman possessions in Spain, were grouped into the Exarchate of Africa by Emperor Maurice. The exarchate prospered, and from it resulted the overthrow of the emperor Phocas by Heraclius in 610. Heraclius briefly considered moving the imperial capital from Constantinople to Carthage. After 640, the exarchate managed to stave off the Muslim Conquest, but in 698, a Muslim army from Egypt sacked Carthage and conquered the exarchate, ending Roman and Christian rule in North Africa. The last provinces of the Western Roman Empire ceased to exist, 222 years after the fall of Rome and the last Western Roman emperor. EVOLUTION OF THE PROVINCE OF AFRICA. The amphitheatre of Thysdrus (modern El Djem). The African provinces were amongst the wealthiest regions in the Empire (rivaled only by Egypt, Syria and Italy itself) and as a consequence people from all over the Empire migrated into the Roman Africa Province, most importantly veterans in early retirement who settled in Africa on farming plots promised for their military service. Historian Theodore Mommsen estimated that under Hadrian nearly 1/3 of the eastern Numidia population (roughly modern Tunisia) was descended from Roman veterans. Even so, the Roman military presence of North Africa was relatively small, consisting of about 28,000 troops and auxiliaries in Numidia and the two Mauretanian provinces. Starting in the 2nd century AD, these garrisons were manned mostly by local inhabitants. A sizable Latin speaking population developed that was multinational in background, sharing the north African region with those speaking Punic and Berber languages. Imperial security forces began to be drawn from the local population, including the Berbers. Abun-Nasr, in his A History of the Maghrib , said that What made the Berbers accept the Roman way of life all the more readily was that the Romans, though a colonizing people who captured their lands by the might of their arms, did not display any racial exclusiveness and were remarkably tolerant of Berber religious cults , be they indigenous or borrowed from the Carthaginians. However, the Roman territory in Africa was unevenly penetrated by Roman culture. Pockets of non-Romanized Berbers continued to exist throughout the Roman period, even in such areas as eastern Tunisia and Numidia. By the end of the Western Roman Empire nearly all of the Maghreb was fully romanized , according to Mommsen in his The Provinces of the Roman Empire and the Roman Africans enjoyed a high level of prosperity. This prosperity (and romanization) touched partially even the populations living outside the Roman limes (mainly the Garamantes and the Getuli), who were reached with Roman expeditions to Sub-Saharan Africa. The willing acceptance of Roman citizenship by members of the ruling class in African cities produced such Roman Africans as the comic poet Terence, the rhetorician Fronto of Cirta, the jurist Salvius Julianus of Hadrumetum, the novelis Apuleius of Madauros, the emperor Septimius Severus of Lepcis Magna, the Christians Tertullian and Cyprian of Carthage, and Arnobius of Sicca and his pupil Lactantius; the angelic doctor Augustine of Thagaste, the epigrammatist Luxorius of Vandal Carthage, and perhaps the biographer Suetonius, and the poet Dracontius. Paul MacKendrick , The North African Stones Speak (1969) , UNC Press, 2000, p. A Roman coin celebrating the province of Africa , struck in AD 136 under the Emperor Hadrian. The personification of Africa is shown wearing an elephant headdress. The prosperity of most towns depended on agriculture. Called the “granary of the empire”, North Africa, according to one estimate, produced one million tons of cereals each year. One-quarter of which was exported. Additional crops included beans, figs, grapes, and other fruits. By the 2nd century, olive oil rivaled cereals as an export item. In addition to the cultivation of slaves, and the capture and transporting of exotic wild animals, the principal production and exports included the textiles, marble, wine, timber, livestock, pottery such as African Red Slip , and wool. The incorporation of colonial cities into the Roman Empire brought an unparalleled degree of urbanization to vast areas of territory, particularly in North Africa. This level of rapid urbanization had a structural impact on the town economy, and artisan production in Roman cities became closely tied to the agrarian spheres of production. As Rome’s population grew, so did her demand for North African produce. This flourishing trade allowed the North African provinces to increase artisan production in rapidly developing cities, making them highly organized urban centers. Many Roman cities shared both consumer and producer model city aspects, as artisanal activity was directly related to the economic role cities played in long-distance trade networks. The urban population became increasingly engaged in the craft and service sectors and less in agrarian employment, until a significant portion of the towns vitality came from the sale or trade of products through middlemen to markets in areas both rural and abroad. The changes that occurred in the infrastructure for agricultural processing, like olive oil and wine production, as trade continued to develop both cities and commerce directly influenced the volume of artisan production. The scale, quality, and demand for these products reached its acme in Roman North Africa. Main article: African Red Slip. African Red Slip flagons and vases, 2nd-4th centuries. A typical plain African Red Slip dish with simple rouletted decoration. The North African provinces spanned across regions rich with olive plantations and potters’ clay sources, which led to the early development of fine Ancient Roman pottery , especially African Red Slip terra sigillata tableware and clay oil lamp manufacture, as a crucial industry. Lamps provided the most common form of illumination in Rome. They were used for public and private lighting, as votive offerings in temples, lighting at festivals, and as grave goods. As the craft developed and increased in quality and craftsmanship, the North African creations began to rival their Italian and Grecian models and eventually surpassed them in merit and in demand. The innovative use of molds around the 1st century BC allowed for a much greater variety of shapes and decorative style, and the skill of the lamp maker was demonstrated by the quality of the decoration found typically on the flat top of the lamp, or discus, and the outer rim, or shoulder. The production process took several stages. The decorative motifs were created using small individual molds, and were then added as appliqué to a plain archetype of the lamp. The embellished lamp was then used to make two plaster half molds, one lower half and one upper half mold, and multiple copies were then able to be mass-produced. Decorative motifs ranged according to the lamp’s function and to popular taste. Ornate patterning of squares and circles were later added to the shoulder with a stylus, as well as palm trees, small fish, animals, and flower patterns. The discus was reserved for conventional scenes of gods, goddesses, mythological subjects, scenes from daily life, erotic scenes, and natural images. The strongly Christian identity of post-Roman society in North Africa is exemplified in the later instances of North African lamps, on which scenes of Christian images like saints, crosses, and biblical figures became commonly articulated topics. Traditional mythological symbols had enduring popularity as well, which can be traced back to North Africa’s Punic heritage. After a period of artisanal, political, and social decline in the 3rd century AD, lamp-making revived and accelerated artistry in the early Christian age to new heights. The introduction of fine local red-fired clays in the late 4th century triggered this revival. African Red Slip ware (ARS), or African Terra Sigillata, revolutionized the pottery and lamp-making industry. ARS ware was produced from the last third of the 1st century AD onwards, and was of major importance in the mid-to-late Roman periods. Famous in antiquity as “fine” or high-quality tableware, it was distributed both regionally and throughout the Mediterranean basin along well-established and heavily trafficked trade routes. North Africa’s economy flourished as its products were dispersed and demand for its products dramatically increased. Initially, the ARS lamp designs imitated the simple design of 3rd- to 4th-century courseware lamps, often with globules on the shoulder or with fluted walls. But new, more ornate designs appeared before the early 5th century as demand spurred on the creative process. The development and widespread distribution of ARS finewares marks the most distinctive phase of North African pottery-making. These characteristic pottery lamps were produced in large quantities by efficiently organized production centers with large-scale manufacturing abilities, and can be attributed to specific pottery-making centers in northern and central Tunisia by way of modern chemical analysis, which allows modern archeologists to trace distribution patterns among trade routes both regional and across the Mediterranean. Some major ARS centers in central Tunisia are Sidi Marzouk Tounsi, Henchir el-Guellal (Djilma), and Henchir es-Srira, all of which have ARS lamp artifacts attributed to them by the microscopic chemical makeup of the clay fabric as well as macroscopic style prevalent in that region. This underscores the idea that these local markets fueled the economy of not only the town itself, but the entire region and supported markets abroad. Certain vessel forms, fabrics, and decorative techniques like rouletting, appliqué, and stamped décor, are specific for a certain region and even for a certain pottery center. If neither form nor decoration of the material to be classified is identifiable, it is possible to trace its origins, not just to a certain region but even to its place of production by comparing its chemical analysis to important northeastern and central Tunisian potteries with good representatives. Governors of Roman Africa. Unless otherwise noted, names of governors in Africa and their dates are taken from T. Broughton , The Magistrates of the Roman Republic , (New York: American Philological Association, 1951, 1986), vol. Inscriptional evidence is less common for this period than for the Imperial era, and names of those who held a provincia are usually recorded by historians only during wartime or by the fasti triumphal. After the defeat of Carthage in 146 BC, no further assignments to Africa among the senior magistrates or promagistrates are recorded until the Jugurthine War (112105 BC), when the command against Jugurtha in Numidia became a consular province. Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (146 BC). Calpurnius Bestia (111 BC). Postumius Albinus (110109 BC). Caecilius Metellus Numidicus (109107 BC). Cornelius Sulla (105 BC). During the civil wars of the 80s and 40s BC , legitimate governors are difficult to distinguish from purely military commands, as rival factions were vying for control of the province by means of force. None known with reasonable certainty for the 90s. Caecilius Metellus Pius (8684 BC). Fabius Hadrianus (84 82 BC). Pompeius Magnus (8279 BC). Licinius Lucullus (7776/75 BC). Manlius Torquatus (69 BC or earlier). Sergius Catilina (6766 BC). Pompeius Rufus (6260/59 BC). Vettius, cognomen possibly Sabinus (5857 BC). Valerius Orca (56 BC). Attius Varus (52 BC and probably earlier; see also below). Considius Longus (5150 BC). Aelius Tubero (49 BC; may never have assumed the post). Attius Varus (seized control again in 49 and held Africa until 48). Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica (47 BC). Porcius Cato (jointly in 47 BC with special charge of Utica). Caninius Rebilus (46 BC). Calvisius Sabinus (45early 44 BC, Africa Vetus). Sallustius Crispus, the historian usually known in English as Sallust (45 BC, Africa Nova). Cornificius (4442 BC, Africa Vetus). Sextius (4440 BC, Africa Nova). Fuficius Fango (41 BC). Aemilius Lepidus (4036 BC). Statilius Taurus (35 BC). Lucius Autronius Paetus (29/28 BC). Marcus Acilius Glabrio (25 BC). Lucius Cornelius Balbus (20/19 BC). Gaius Sentius Saturninus (14/13 BC). Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (13/12 BC). Publius Quinctilius Varus approx (9/84 BC). Lucius Passienus Rufus approx c. Cossus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus c. Lucius Caninius Gallus c. Lucius Aelius Lamia (1516). Gaius Vibius Marsus (2629). Marcus Junius Silanus (2935). Gaius Rubellius Blandus (3536). Servius Cornelius Cethegus (3637). Reign of Gaius Caligula. Lucius Calpurnius Piso (3839). Lucius Salvius Otho (4041). Quintus Marcius Barea Soranus (4143). Servius Sulpicius Galba (4446). Marcus Servilius Nonianus (4647). Titus Statilius Taurus IV. Marcus Pompeius Silvanus Staberius Flavianus (5356). Quintus Sulpicius Camerinus Peticus (5657). Gnaeus Hosidius Geta (5758). Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus (6263). Titus Flavius Vespasianus (6364). Gaius Vipstanus Apronianus (68). Lucius Minicius Natalis (121). Reign of Antoninus Pius. Titus Prifernius Paetus Rosianus Geminus (140141). Sextus Julius Major (141142). Publius Tullius Varro (142143). Lucius Minicius Natalis Quadronius Verus (153154). Lucius Hedius Rufus Lollianus Avitus (157158). Reign of Marcus Aurelius. Sextus Cocceius Severianus (161163). Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus (164). Marcus Antonius Zeno (164165). Titus Sextius Lateranus (168/169). Gaius Vettius Sabinianus Julius Hospes c. Reign of Septimius Severus. Publius Cornelius Anullinus (193). Pollienus Auspex (Between 194 and 200). Marcus Claudius Macrinius Vindex Hermogenianus (Between 194 and 200). Sextus Cocceius Vibianus (Between 194 and 200). Cingius Severus (Between 194 and 197). Lucius Cossonius Eggius Marullus (198199). Marcus Ulpius Arabianus c. Gaius Julius Asper (Between 200 and 210). Marcus Umbrius Primus c. Marcus Valerius Bradua Mauricus? Titus Flavius Decimus (209). Gaius Valerius Pudens (Between 209 and 211). Publius Julius Scapula Tertullus Priscus (212213). Appius Claudius Julianus (Between 212 and 220). Gaius Caesonius Macer Rufinianus (Between 213 and 215). Marius Maximus (Between 213 and 217). Lucius Marius Perpetuus c. Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus c. Reign of Alexander Severus. Gaius Octavius Appius Suetrius Sabinus c. Reign of Maximinus Thrax. Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus Africanus (237). Reign of Gordian III. Lucius Caesonius Lucillus Macer Rufinianus c. Reigns of Valerian and Gallienus. (Between 259 and 261). Vibius Passienus (Between 260 and 268). Lucius Naevius Aquilinus (Between 260 and 268). Sextus Cocceius Anicius Faustus (Between 265 and 268). Lucius Caesonius Ovinius Manlius Rufinianus Bassus c. Gaius Julius Paulinus (283). Governors are directly chosen by the Emperors, without Roman Senate approval. Titus Claudius Aurelius Aristobulus (290294). Titus Flavius Postumius Titianus (295296). Lucius Aelius Helvius Dionysius (296300). Iulianus, possibly Amnius Anicius Julianus (301302). Gaius Annius Anullinus (302305). Gaius Caeionius Rufius Volusianus (305306). Cezeus Largus Maternianus (333-336). Quintus Flavius Maesius Egnatius Lollianus (336-337). Fabius Aconius Catullinus Philomathius (vicarius , 338339). Sextus Claudius Petronius Probus (358-359). Quintus Clodius Hermogenianus Olybrius (361-362). Claudius Hermogenianus Caesarius (365-366). Julius Festus Hymetius (366-368). Sextius Rusticus Julianus (371-373). Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (373-374). Decimius Hilarianus Hesperius (April 376-October 377). Thalassius (October 377-April 379). Flavius Afranius Syagrius (379-380). Helvius Vindicianus (380-381; possibly 382-383). Virius Audentius Aemilianus (382-383; possibly 381-382). Felix Juniorinus Polemius (388-389). Latinius Pacatus Drepanius (389-390). Flavius Rhodinus Primus (391-392). Aemilius Florus Paternus (392-393). Gabinius Barbarus Pompeianus (400401). Rufius Antonius Agrypnius Volusianus (404-405). Flavius Pionius Diotimus (405-406). Aelius Pompeius Porphyrius Proculus (407-408). Sentius Fabricius Iulianus (412-414). Aurelius Anicius Symmachus (415). L ucius Septimius Severus (or rarely Severus I) (April 11, 145/146-February 4, 211) was a Roman general, and Roman Emperor from April 14, 193 to 211. He was born in what is now the Berber part of Rome’s historic Africa Province. Septimius Severus was born and raised at Leptis Magna (modern Berber , southeast of Carthage , modern Tunisia). Severus came from a wealthy, distinguished family of equestrian rank. Severus was of Italian Roman ancestry on his mother’s side and of Punic or Libyan -Punic ancestry on his father’s. Little is known of his father, Publius Septimius Geta , who held no major political status but had two cousins who served as consuls under emperor Antoninus Pius. His mother, Fulvia Pia’s family moved from Italy to North Africa and was of the Fulvius gens, an ancient and politically influential clan, which was originally of plebeian status. His siblings were a younger Publius Septimius Geta and Septimia Octavilla. Severuss maternal cousin was Praetorian Guard and consul Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. In 172, Severus was made a Senator by the then emperor Marcus Aurelius. In 187 he married secondly Julia Domna. In 190 Severus became consul , and in the following year received from the emperor Commodus (successor to Marcus Aurelius) the command of the legions in Pannonia. On the murder of Pertinax by the troops in 193, they proclaimed Severus Emperor at Carnuntum , whereupon he hurried to Italy. The former emperor, Didius Julianus , was condemned to death by the Senate and killed, and Severus took possession of Rome without opposition. The legions of Syria , however, had proclaimed Pescennius Niger emperor. At the same time, Severus felt it was reasonable to offer Clodius Albinus , the powerful governor of Britannia who had probably supported Didius against him, the rank of Caesar, which implied some claim to succession. With his rearguard safe, he moved to the East and crushed Niger’s forces at the Battle of Issus. The following year was devoted to suppressing Mesopotamia and other Parthian vassals who had backed Niger. When afterwards Severus declared openly his son Caracalla as successor, Albinus was hailed emperor by his troops and moved to Gallia. Severus, after a short stay in Rome, moved northwards to meet him. In the Battle of Lugdunum , with an army of 100,000 men, mostly composed of Illyrian , Moesian and Dacian legions, Severus defeated and killed Clodius Albinus, securing his full control over the Empire. Severus was at heart a soldier , and sought glory through military exploits. In 197 he waged a brief and successful war against the Parthian Empire in retaliation for the support given to Pescennius Niger. The Parthian capital Ctesiphon was sacked by the legions, and the northern half of Mesopotamia was restored to Rome. His relations with the Roman Senate were never good. Severus ordered the execution of dozens of Senators on charges of corruption and conspiracy against him, replacing them with his own favorites. He also disbanded the Praetorian Guard and replaced it with one of his own, made up of 50,000 loyal soldiers mainly camped at Albanum , near Rome (also probably to grant the emperor a kind of centralized reserve). During his reign the number of legions was also increased from 25/30 to 33. He also increased the number of auxiliary corps (numerii), many of these troops coming from the Eastern borders. Additionally the annual wage for a soldier was raised from 300 to 500 denarii. Although his actions turned Rome into a military dictatorship , he was popular with the citizens of Rome, having stamped out the rampant corruption of Commodus’s reign. According to Cassius Dio, however, after 197 Severus fell heavily under the influence of his Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus , who came to have almost total control of most branches of the imperial administration. Plautianus’s daughter, Fulvia Plautilla , was married to Severus’s son, Caracalla. Plautianuss excessive power came to an end in 205, when he was denounced by the Emperor’s dying brother and killed. The two following praefecti , including the jurist Aemilius Papinianus , received however even larger powers. Campaigns in Caledonia (Scotland). Starting from 208 Severus undertook a number of military actions in Roman Britain , reconstructing Hadrian’s Wall and campaigning in Scotland. He reached the area of the Moray Firth in his last campaign in Caledonia, as was called Scotland by the Romans.. In 210 obtained a peace with the Picts that lasted practically until the final withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain, before falling severely ill in Eboracum (York). He is famously said to have given the advice to his sons: “Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men” before he died at Eboracum on. Upon his death in 211, Severus was deified by the Senate and succeeded by his sons, Caracalla and Geta , who were advised by his wife Julia Domna. The stability Severus provided the Empire was soon gone under their reign. Though his military expenditure was costly to the empire, Severus was the strong, able ruler that Rome needed at the time. He began a tradition of effective emperors elevated solely by the military. Severus was also distinguished for his buildings. Apart from the triumphal arch in the Roman Forum carrying his full name, he also built the Septizodium in Rome and enriched greatly his native city of Leptis Magna (including another triumphal arch on the occasion of his visit of 203). Christians were persecuted during the reign of Septimus Severus. Severus allowed the enforcement of policies already long-established, which meant that Roman authorities did not intentionally seek out Christians, but when people were accused of being Christians they could either curse Jesus and make an offering to Roman gods , or be executed. Furthermore, wishing to strengthen the peace by encouraging religious harmony through syncretism , Severus tried to limit the spread of the two quarrelsome groups who refused to yield to syncretism by outlawing conversion to Christianity or Judaism. Individual officials availed themselves of the laws to proceed with rigor against the Christians. Naturally the emperor, with his strict conception of law, did not hinder such partial persecution, which took place in Egypt and the Thebaid , as well as in Africa proconsularis and the East. Christian martyrs were numerous in Alexandria cf. Clement of Alexandria , Stromata , ii. 20; Eusebius , Church History , V. No less severe were the persecutions in Africa, which seem to have begun in 197 or 198 cf. Tertullian’s Ad martyres , and included the Christians known in the Roman martyrology as the martyrs of Madaura. Probably in 202 or 203 Felicitas and Perpetua suffered for their faith. Persecution again raged for a short time under the proconsul Scapula in 211, especially in Numidia and Mauritania. Later accounts of a Gallic persecution, especially at Lyon , are legendary. In general it may thus be said that the position of the Christians under Septimius Severus was the same as under the Antonines ; but the law of this Emperor at least shows clearly that the rescript of Trajan. Had failed to execute its purpose. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order? When should I leave feedback? Once you receive your order, please leave a positive. Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. The item “SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS 207AD AFRICA Elephant Lion Ancient Silver Roman Coin i52147″ is in sale since Saturday, January 26, 2019. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ Ancient\Roman\ Imperial (27 BC-476 AD)”. The seller is “highrating_lowprice” and is located in Rego Park, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Composition: Silver

- Ruler: Septimius Severus